Earlier this year, a question was posed to me – one that lodged itself under my skin, not because it was profound, but because it disappointed me.

“Should learning be easy or hard?”

I’ve never been one for deceptively simplistic binaries. To me, this question revealed something important: a conceptual flattening of what learning feels like, requires, and becomes in a K–12 classroom. To be fair, perhaps the questioner meant to provoke thought, to generate from my response something richer. Perhaps it was a misfired provocation or wording in the moment. Or perhaps it simply surfaced a wider misconception: that learning should be either frictionless, or conversely, punishing.

It should be neither.

Our work as K-12 teachers isn’t to make learning “easy” or “hard.” I suspect that should be true in the VET or Higher Education contexts as well.

We have so many students who already find barriers in their path of learning. It is the responsibility of educators to engage them in learning. To invite them. To support them. Learning should not be easy (frictionless) or hard (punishing). There must be another way…

I can’t speak for all contexts but, in the History classroom, I’d propose that it’s important that learning should be meaningful. To me, that means something beyond easy or hard. For my students, the journey towards learning that ‘makes meaning’ is one in which information, experiences, and activities should be accessible, purposeful, and appropriately challenging.

To me the job of the teacher is to create spaces where students can do the real cognitive work without being crushed by it or bypassing it entirely with tools that take too much of the cognitive load from them.

This is where cognitive friction comes in – not as obstacle, but as the generative tension where understanding is forged. Cognitive friction has always been important but has perhaps been too often overlooked by too many educators. With Generative AI in the K-12 classroom, monitoring and regulating this friction becomes not just important, but essential.

But how do we do that?

This brings me to my hoche poche of observations on the year that was.

‘We’re building the plane as we fly it’

MIT’s Justin Reich and his team refer this phrase in the preface to their excellent Guide to AI in Schools: Perspectives for the Perplexed. They point out that teachers are teaching with an arrival technology when they encounter AI in the classroom. They remind us that we’re all feeling our way forward when we talk about teaching with AI.

No one in 1905 could have said the best way to build a plane or fly one or operate an aviation system. And no one in 2025 can say how best to manage AI in schools. It will take our school systems – our educators, our policymakers, our researchers, our parents, our governments – some number of years to try a range of approaches and suss out which ones work best in which contexts… Unfortunately, schools can’t wait to figure out how to manage the arrival of generative AI.

So rather than give you a prescriptive approach to how to approach 2026 based upon my classroom experiences of 2025, I hope you’ll take this post as a reflection for me that may have some value in your context.

Start broad and then narrow…

I’d suggest that educators on the journey to work out how best to teach with AI (and that’s all of us), would do well to start from some broad principles, then to try to identify a framework for their practice, before coming up with specific approaches.

Before launching forward into programs of ‘implementing AI’ in their school, educators would benefit from some big picture reflection. I think we need to ‘know our why’. We need to think about what we value in education and what our purpose is within our subject specific domains. Whatever we do after that, we need to hold true to those values. Use the emerging research to guide you forward, to help your navigate, but know your destination.

With that as a starting point, let me point you to:

- My Generative AI Principles article written with Petrea Redmond and Alison Bedford of UniSQ. It represents an early articulation of how I like to think about AI pedagogically, ethically, and practically.

- My Bubble and Burner Model article which presents a visual metaphor for safely scaffolding and sequencing AI integration in ways that protect cognitive friction and guide teacher action.

- A growing list of classroom strategies and routines – what I now refer to as my Ways of Working with AI (WoW-AI!) – including “2 x I + V”, “Plus 3”, “CEC”, “CELs”, and “Quest-Questioning.” These are explored in more depth in the articles and throughout this blog.

These principles, frameworks and tools don’t just support the ‘how’ of AI-infusion — they anchor the why. Their aim was to build a broad and adaptive base from which we might develop appropriate subject specific pedagogical strategies that are fit for purpose in an age of AI. These further strategies will be part of my emerging AiTLAS in 2026.

The goal of all of these principles, frameworks, and tools is not to make learning easy or hard but meaningful – accessible, purposeful, and appropriately challenging.

From Principles to Praxis: Building the AiTLAS Project

The early Generative AI Principles, developed in 2024–2025 through practitioner-led reflexive research, gave shape to the first questions:

- How do we teach students to use AI ethically and intentionally?

- How do we build discernment, not just efficiency?

- And how do we ensure that AI use contributes to the development of the whole human — not just the production of a more polished paragraph?

These weren’t abstract musings. They were born of practice – from moments of watching students slip too easily into cognitive outsourcing, from lessons where AI unlocked deeper insight, and from those times where it all fell flat.

Speaking of my students, you can hear their voice HERE.

That’s where the Bubble and Burner Model of AI-Infusion came in — a metaphor-driven framework to help teachers visualise the dynamic flow of learning when AI is present in the room. The Bubble metaphor protects the learner; the Burner metaphor empowers the teacher. Together, they scaffold the shifting relational space between human cognition and machine capacity.

From this emerged the AiTLAS Project— a collection of WoW-AIs, strategies, methodologies, and pedagogical decision-points for classrooms.

5 Insights from a(nother) year of teaching & learning with AI

So, here’s five insights I’ve taken from my classroom experiences this year…

1. AI works, if you teach it – students aren’t “naturally fluent” with it.

Despite the rhetoric, students aren’t digital natives and are not “born fluent” with AI. They may generate content quickly, but without guidance, they often miss the point of learning. This year showed me that a concern for cognitive friction needs to be taught — patiently, explicitly, and strategically. Like teachers, students need to ‘know their why’ also.

Tools like 2 x I + V, Plus3, CEC, and Quest-Questioning provided critical scaffolds for students to become thoughtful users, not passive consumers. These are not digital natives – they are digital learners, and it’s our role to guide that learning.

2. Generative AI must be embedded in a values‑based, human‑centred pedagogy — not treated as a shortcut or gimmick.

The most powerful AI work I’ve seen in the classroom didn’t just “get the job done” – it deepened students’ sense of purpose. Teaching with AI must sit inside an ethical, human-centred approach that values whole-person development. My practice increasingly draws from Indigenous pedagogies (like Tyson Yunkaporta’s 8ways) and the schools values of integrity, compassion and justice. When students used AI their goal was grounded in working transparently within a values framework to share stories more richly, uncover more insights, unveil further depths of meaning, explore multiple perspectives, engage in thoughtful self-reflection, communicate more effectively. It wasn’t just academic performativity — it aspired to be deeply human.

3. AI can create space – but only if teachers act with wisdom

AI can give us time back – but what matters is what we do with it.

This year, I’ve leaned heavily into flipped learning structures to reclaim class time for discussion, synthesis, and sense-making. But this only works when we pair AI use with intentional cognitive friction. Students don’t grow from smooth answers – they grow from the productive tension of wrestling with ideas. While AI can increase accessibility and allow students to differentiate for learning, we need to keep the challenge and the passion alive.

The strategies I’ve used – Plus 3, CEC, and carefully designed checks for understanding (developing Chains of Evidence of Learning or CELs) – help ensure that we use AI to create depth, not just speed.

If we gain time through the use of technology, the question is how best to use that gain. I propose that we use that time to slow down, reflect, and deepen learning.

4. We need new assessment paradigms.

AI calls into question the very nature of what is assessed and why we assess it.

If a machine can produce a polished final draft or a homework paragraph, what does an authentic representation of student learning look like?

Increasingly, I’ve shifted towards tracing students’ thinking over time — what I call Chains of Evidence of Learning (CELs). These chains should be collected over time. As Jason Lodge argues, we need to see assessment (and learning) as a process not a product. We need to clarify how we best collect evidence of students’ authentic growth in learning, their reflection, and their sense-making.

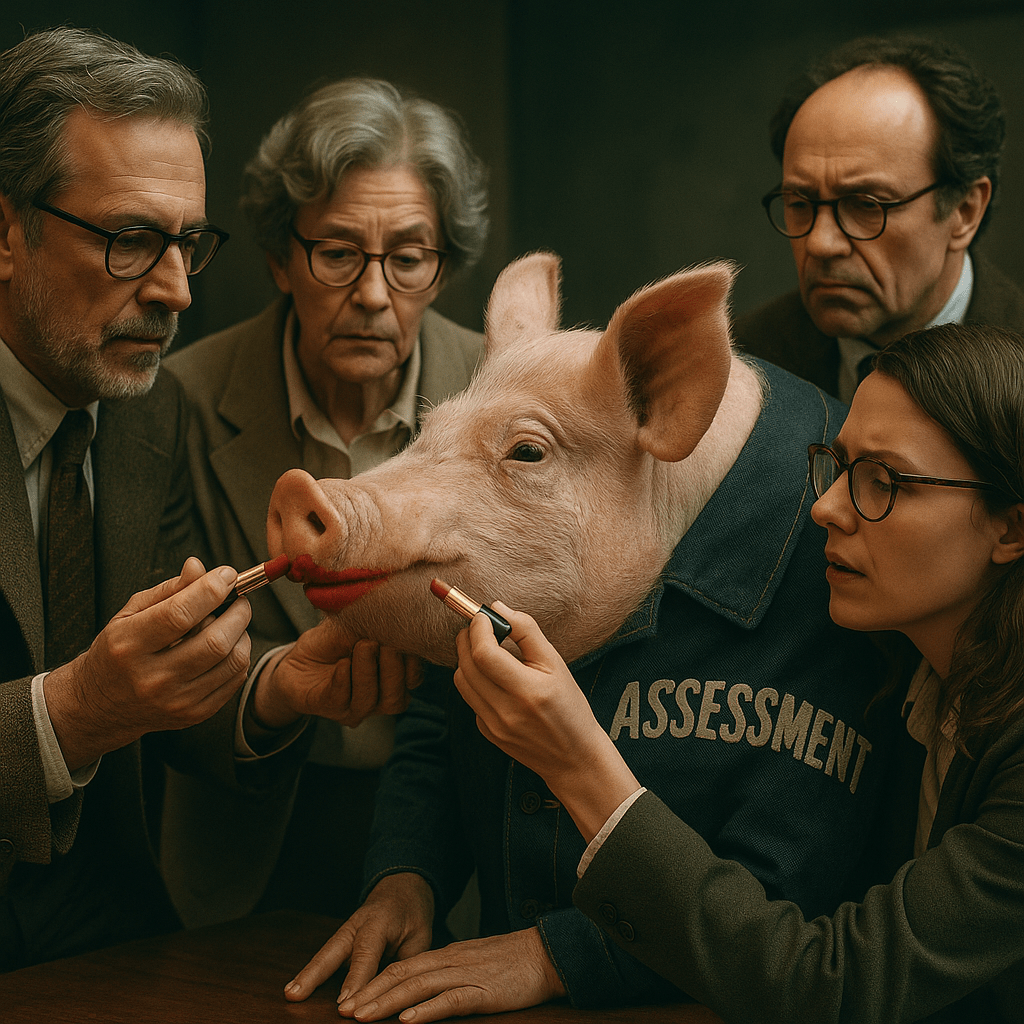

While we are grappling with how best to adjust assessment processes in an AI age, I wonder if we are seeing AI challenge machine age assessment approaches at their very core. Perhaps it’s time to radically overhaul the very nature of many assessment tasks so as to place what we truly value at the heart of our schools. Perhaps tinkering with the edges of assessment is like ‘putting lipstick on a pig’.

It’s time for education authorities to reimagine assessment: to support the design and documentation of process-based learning that AI cannot fabricate.

5. Teaching with AI requires leadership, capacity-building and intention -for both teachers and institutions.

If schools want meaningful, ethical, and sustainable AI integration, it’s not enough to hand out tools or buy product subscriptions… and it won’t happen by osmosis!

Teachers need time to learn, space to experiment, and leaders who understand that pedagogy must drive the tech – not the other way around. Using AI well is a messy and time-consuming space to wade into… and rather than wading we are running. Chasing an ever-moving target. In such a VUCA environment, teachers require a chance to stop and reflect.

To teach well with AI means that teachers, especially in K-12 History, will need to build their capacity to engage with students, and to build class practices, that celebrate, respect, reflect and cultivate a richness in humanity. We’ll need ways to draw out and amplify student voice and agency. These priorities take the development of personal and professional capacity – a deep authenticity – in teachers that is far from the performativity of much classroom practice of the industrial age.

… and all of this rests upon educational leadership at every level have the strategic vision – and a community – that supports the thoughtful integration of AI into learning.

Conclusion: The Pig, the Provocation, and the Point

There’s an old saying about putting lipstick on a pig – and this year, I’ve noticed some institutions scrambling to somehow assimilate AI-era disruption into old assessment regimes, I’ve seen more than a few porcine makeovers. Without reflection and vision, that’s what many education authorities and institutions are doing when they talk of integration of AI.

The truth is, even though we’re building this plane as we fly it, we can’t just dress up our existing practices and call it an AI transformation. Assessment, while important, is only one part of the conversation — and too often, it becomes the only conversation and a distraction from what matters most… LEARNING.

Because when I look back on everything I’ve explored this year – from flipped learning to ethical AI use, from multimodal tasks to Chains of Evidence – I keep returning to that one misfired question: “Should learning be easy or hard?” And I return to the same conviction: learning should be meaningful.

In my History classroom, and in any K–12 space where young people are thinking, wondering, creating, and struggling – learning should be accessible, purposeful, and appropriately challenging. Our job is to design the conditions where students can do the real cognitive work – not be crushed by it, and not bypass it with tools that offload too much of the load.

This is the work of teaching in an AI age: not to make learning smooth, but to make it real. Not to eliminate friction, but to regulate it wisely. Because it’s in that friction that the learning lives…

It’s in the slow learning, in that deeply human space of connection and community, where we both struggle and celebrate, where we find learning engaging and inviting that we get to discover voices, build agency, and amplify our humanity.

The work of teaching and learning in an AI age is too important for narrow conversations that are limited to assessment items or a porcine makeover for industrial models of schooling.

You must be logged in to post a comment.