How do we meaningfully design assessment of and for learning when the presence of AI tools fundamentally changes the game?

Earlier this term, I was invited to present to a group of school curriculum leaders who are preparing to reimagine assessment for the 2026 school year. The timing is both exciting and daunting. These leaders find themselves on the frontlines of a rapidly shifting educational landscape, grappling with the complex interplay of generative AI, cognitive development, academic integrity, digital equity, and evolving pedagogies.

As they begin a months-long journey of redesigning their school’s assessment programs, many are rightly asking:

How do we meaningfully redesign assessment when the presence of AI tools fundamentally changes the game?

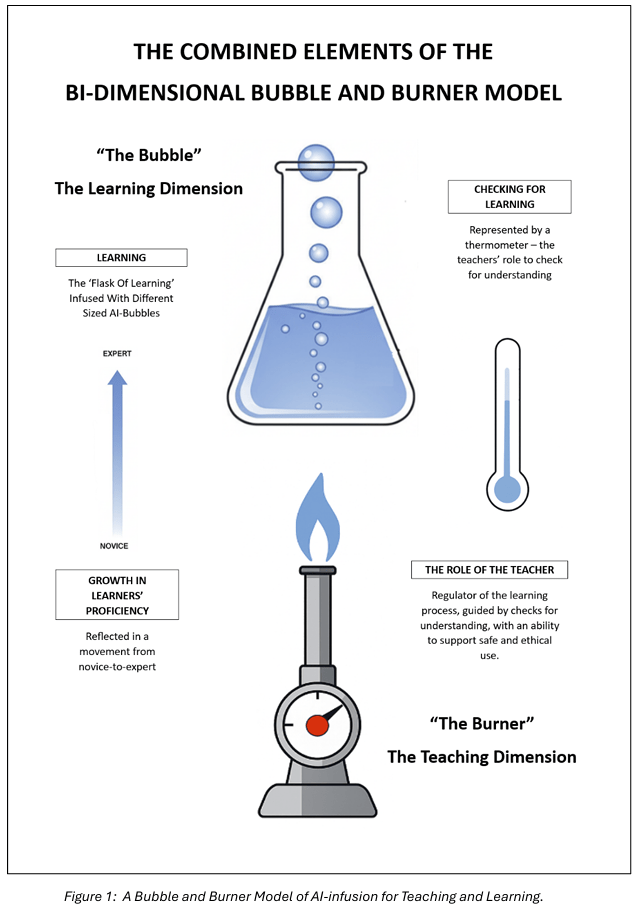

In a world where formal assessment can seem to drive the agenda of schools, this question is fundamental. It is also an aspect at the heart of classrooms that the Bubble and Burner model I shared with them does not seek to address. That model that urges us to reflect on how we scaffold student growth (the Bubble) and regulate cognitive heat through thoughtful teacher intervention (the Burner). It’s a framework for visualising learning and teaching. In most schools, ‘assessment’ is a different beast.

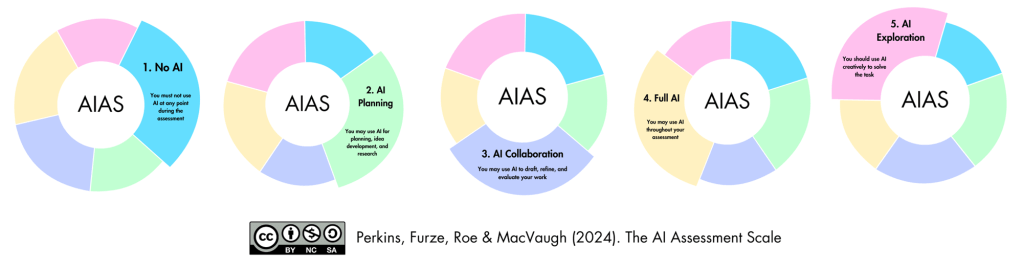

Used well, the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS), first developed by Perkins, Furze, Roe, and MacVaugh in 2024, offers many educators a way forward in their efforts to reimagine the design of assessment. But if used superficially (without enough thinking around the levels of AI use it describes) in ways not intended by its designers, the scale can be performative and misleading in the classroom.

Assessment of and for Learning

Before discussing the AIAS at any length, let’s pause to clarify these two key terms:

- Assessment of learning evaluates what students have learned. It is typically summative, providing a snapshot of achievement against standards or outcomes.

- Assessment for learning is formative. It supports student growth by providing timely feedback, shaping learning pathways, and encouraging reflection.

In History and Humanities classrooms, where take-home assignments can often serve both purposes, it is crucial to consider how generative AI changes the learning conditions. Used wisely, assessment of and for learning is an effective measure of skill acquisition, knowledge and understanding. These are core elements of my Bubble and Burner model and are considered as core responsibilities of teachers in the AI-infused classroom but we, again, must ask some important questions: Can a traditional take-home assignment still claim to be an accurate assessment of learning if students have access to the use of AI? Can the product created by students still be for learning if it bypasses the cognitive friction, the struggle, missteps, and the authentic engagement?

This is precisely where Perkins, Roe, and Furze’s (2025) most powerful insights come into play.

What Is the AIAS?

The Artificial Intelligence Assessment Scale (AIAS), developed by Perkins, Roe, Furze, and MacVaugh, emerged in late 2023 as a framework to support the ethical and educationally sound integration of generative AI (GenAI) into assessment practices. Now in what I call version 3+, the AIAS proposes five non-hierarchical levels that educators can use to conceptualise the role of AI in a given task: from No AI (1) through to AI Exploration (5). Crucially, the scale is not about compliance or restriction. Rather, it is designed to help educators consider how the presence or absence of AI changes the nature of the learning and assessment experience.

The AIAS has spread rapidly – adopted in over 350 institutions and translated into more than 30 languages – but with this uptake have come misunderstandings and misuse. As highlighted in my curriculum leaders’ presentation, some versions circulating in schools represent what William might call ‘lethal mutations’: static hierarchies, performative use of numbering systems, or the assumption that the AIAS implies that AI is inherently a threat to be stopped.

In reality, the AIAS invites us to think with nuance and context, redesigning assessments that support student growth, rather than reacting with fear. Used properly, I’d suggest that the AIAS is less like a traffic light system controlling AI use than it is a way of engaging with a process of regulating the temperature of learning through the thoughtful design of assessment.

Three Critical Misconceptions to Avoid

In their 2025 paper, Perkins, Roe and Furze identify five aspects of the AIAS that they believe K-12 teachers and educators needs further guidance on. This blog will very briefly address three of these that I believe are most worth noting by History and HASS educators. I will return to these ideas, and others, in future blogs.

The Illusion of Enforcement

“The first major misconception is that the AIAS can be used to label an existing assessment without considering the possibility of enforcement. … In an unsecured essay assessment, there is no realistic way to ensure that no AI technologies are used throughout the process… Using this kind of approach ultimately creates conditions that are purely performative… Programmes of study should often (and in some cases must) contain ‘No AI’ assessments, but these need to be practical and pragmatic.” (p. 3)

Too many take-home aspects of assignments are now being labelled as ‘No AI’ without any change to the conditions or scaffolding around the task set. In History especially, this creates performative dishonesty – students are positioned by such requirements to either act in ways that might remove useful tools from their learning process, make learning less accessible to them, place them at disadvantage to their peers who use AI regardless of the unenforceable instruction, or to act in unethical and opaque ways. Instead of this, if we need a genuine No AI task, it must be in a context that allows for authentic enforcement: in-class, time-limited, scaffolded. Perhaps if it’s considered important for a take-home assignment to have ‘No AI’, the design might consider at what phase that ‘No AI’ experience might be – and at what stage other levels of the scale might be most appropriate.

Guidance, Not Gridlock

“[T]he levels of the AIAS are not prescriptive; they are guiding… The interpretation of this is up to individual educators, and finer distinctions can be co-defined by the educator, institution, and learner… [They are] ways of thinking about how assessment can be reconfigured to support the assessment of and for learning… adapted and altered to suit the on-the-ground conditions.” (pp. 4-5)

This point should resonate with every teacher in the humanities. Context is everything. The same history assignment might contain multiple levels: there may be a space for ‘No AI’ in-class source analysis to build foundational thinking; a GenAI ‘Planning’ throughout a research phase; and AI ‘Collaboration’ as an essay reflecting historical inquiry is developed. Let the learning sequence dictate the scale, not the other way around. What is important here is developing an evidence chain of learning (more on that in a future blog) and the ethics of transparency – these underpin the validity of the assessment item.

The Design Imperative

“Assessment design is difficult, time-consuming, and requires significant bureaucratic considerations… it might be tempting for educators to just assign an AIAS level… without making any changes to the assessment brief, rubric, or student guidance… The AIAS is primarily an assessment design tool, not an assessment security tool.” (p. 4)

In History faculties, this is particularly relevant.

If you permit AI, then the assignment must be redesigned to assess how students used it – their choices, reasoning, prompts, and iterations. Grade the process, not just the product. This means creating new rubrics, evidence trails, and scaffolds that guide students in ethical, thoughtful AI engagement. As suggested above, if you wish an assessment to be ‘No AI’ how will you design high-quality assessment to that end in ways where the condition of ‘No AI’ can be enforced in accordance with research-grounded best practices around assessment.

“AI has been used as an excuse to move towards more end-of-unit, supervised, timed examinations, since those assessments are seen as both ‘more secure’ and reflect the formal exams that often come at the end of secondary schooling. However, this approach contradicts the best practices in assessment design. Valid assessments must be equitable, authentic, replicate real-world and practical skills, vary in form and mode, and enable teachers to build comprehensive pictures of students over time. While examinations are secure, they fail to meet these criteria.” (p.6)

‘We Are Here’ – Make sure your thinking reflects the latest commentary on the AIAS…

While being aware of the valuable earlier iterations of the AIAS, teachers should be aware

that some aspects of these models are now being misapplied.

Perhaps a way to avoid some of the unintended ‘lethal mutations’ to the AIAS is to ensure that

you are referring to what I call Version 3+ of the AIAS.

Version 3+, to me is characterised by use of (1) the ‘circular model’ created by Perkins, Furze et al. in combination with (2) the commentary in the extremely valuable How (not) to use the AI Assessment Scale (September 14 2025).

From Bubble and Burner to Better Design

My recent Bubble and Burner model was about how to visualise the process of teaching and learning in AI -infused classrooms. It did not go so far as exploring assessment or teaching strategies to assist in a process of collecting chains of learning evidence. This is work for the future. In my model, the Bubble reminds us that students need space to grow their metacognition, critical discernment, and understanding of historical process. The cognitive offloading risks associated with AI are too great unless we, as teachers, ‘regulate the burner’ of learning – the challenge, the struggle, the friction, and the reflection. Teachers must become regulators of AI heat: adjusting, checking, guiding the use of AI within learning. In this conceptualisation, the AIAS, then, is an important tool for teachers. Used with discernment, it helps us tune learning experiences – and assessment experiences – to ensure students cognitively engage rather than offload.

Practical Takeaways for History Teachers

Moving forward from this point, as teachers and departments begin to consider the nature of their assessment in 2026, perhaps the following pointers might be helpful.

Take a look at your current departmental assessment practices. Think about how well they align with the best practices of assessment, the best practices of your subject area discipline, and the realities of the AI age we live in. Have the difficult conversations about your current and past practices.

- Audit your tasks honestly: How fit for purpose are they? In light of the most recent version of the AIAS (i.e. September 2025 – what I call v3+), is it best practice? As you audit your current assessment items, perhaps this audit tool may be of interest to you. Use it thoughtfully as a tool for reflection – not slavishly!

- Design for process, not product: Does your assignment process allow for the collection of chains of evidence of learning? Does it include a requirement for students to share public links to their chat threads with AI? Does it feature non-AI moments where students engage in reflective commentaries (both asynchronous and face-to-face, group and individual) and multiple checkpoints? Does it allow teachers plenty of opportunities to get to know their learners and how they learn – to sit with them, guide them, engage with them as they struggle?

- Use multiple levels within a unit of learning: Does the assignment recognise that different levels of AI usage may be appropriate at different times? How does it structure that design into the learning process and assessment practices?

- Make it visible: Clearly define the expectations of staff and students in plain accessible terms. Work through these expectations, and the reasoning behind them, with students – and members of your faculty. Use these expectations – and a full reading of latest discussions of the latest iterations of the AIAS – as a tool for dialogue…

Ultimately, the challenge for 2026 is not technological. It is pedagogical. It’s human.

The real task is not to contain AI, but to design learning experiences that develop students’ historical thinking, ethical reasoning, and human judgement in a world with AI.

That work may be hard. But it is important.

You must be logged in to post a comment.