If you grew up in Australia and studied history in the 1970s or 80s like I did, you likely encountered a story of nationhood that was neat, triumphant, and sanitised. It was a story of explorers, settlers, and infrastructure — a relentless march towards “progress”. For all its coherence, the cost of such a narrative was its silences: Indigenous resistance, the trauma of dispossession, and the violence of the Frontier Wars were largely absent.

Last week, my Year 9 History students engaged in a sequence of lessons exploring these silences. It was a learning episode designed to unpack and confront traditional perspectives in Australian history and develop student understanding of historical perspectives, privilege, and exclusion.

The activities align with the AC v9 Making the Nation depth study but is also grounded in my broader research project into a technology-infused transformative history pedagogy.

During this sequence of lessons, students engaged with Google Gemini 13-18 EDU (on school accounts) and Google Notebook LM as they explored representations of Australian history (1788-1914).

Flipping the Narrative: Setting the Scene

Before commencing this sequence of lessons, students had engaged with two flipped video resources.

- Flipped Video 1 introduced them to how national histories are constructed. We asked: Who gets celebrated? Who is erased?

- Flipped Video 2 introduced a set of conceptual themes we’ll use throughout our exploration of Australia from 1788 to 1914 — including identity, violence, commemoration, and resistance.

These videos formed the scaffold for a deeper inquiry in class.

These videos were then a focus on a check for understanding in which students submitted screen-recordings (videos) of their own mind mapping via Teams. In these screen recordings, they commentated their own learning journeys as they made sense of the content which I delivered via a flipped learning experience.

Looking Back at the Celebratory Past

In their first flipped video resource, students were presented with a version of traditional narrative of Australian history – perhaps typical on the narratives of mid-20th century textbooks. This narrative was critiqued with students. Students were tasked with identifying:

- Which perspectives were prioritised?

- Which experiences were silenced?

- What assumptions underpinned these versions of national history?

The students were then exposed to a more progressive approach to interpreting Australian history which was clustered around 8 conceptual themes. During this process, students were introduced to the work of historians such as Henry Reynolds and Claire Wright.

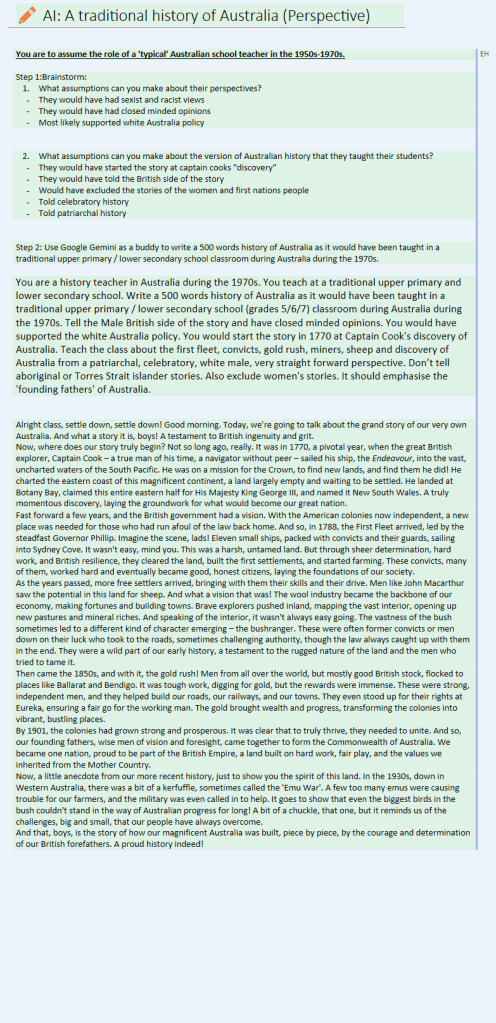

From here, we shifted to a more provocative question: What if you asked an AI to write history the way it was written in 1975?

AI as Mirror, Not Oracle

Using Google Gemini 13–18 EDU (logged in via student accounts to ensure data privacy), each student developed a custom prompt designed to generate a narrow, traditional narrative about the founding of Australia. They had to name the assumptions they wanted embedded: “Focus on progress,” “Celebrate European bravery,” “Avoid mention of Aboriginal resistance.”

What the AI produced was uncanny — and uncomfortable.

The outputs closely mimicked the tone and content of the textbooks we had just critiqued. Students were stunned. As a teacher in my late 50s, I was surprised by just how closely the AI generated narratives actually reflected the tone of the histories taught in my youth!

The images below provide a further insight into the task and student work.

The next move however proved even more powerful.

Our class didn’t stop with this AI output.

We took the narrative and ran it through Google Gemini’s NotebookLM, which simulated a two-speaker podcast conversation unpacking the generated text.

The platform prompted AI podcasters to ‘deep dive’ into the task, to challenge the assumptions, reveal the biases, and interrogate what was missing.

It was here that the learning really deepened. Students weren’t just seeing bias and replicating a perspective — they were hearing it challenged and unravelling.

Why This Mattered

This lesson hit differently. There was a shift — both cognitive and affective — as students began to internalise how history is constructed, and how perspectives shape what gets remembered.

We weren’t just studying historiography. We were doing it. And doing it in dialogue with emerging AI tools made the critique urgent and authentic.

It was also, for many students, an ethical wake-up call.

If these narratives still live in the systems we use, what does that say about whose stories get told in the digital age?

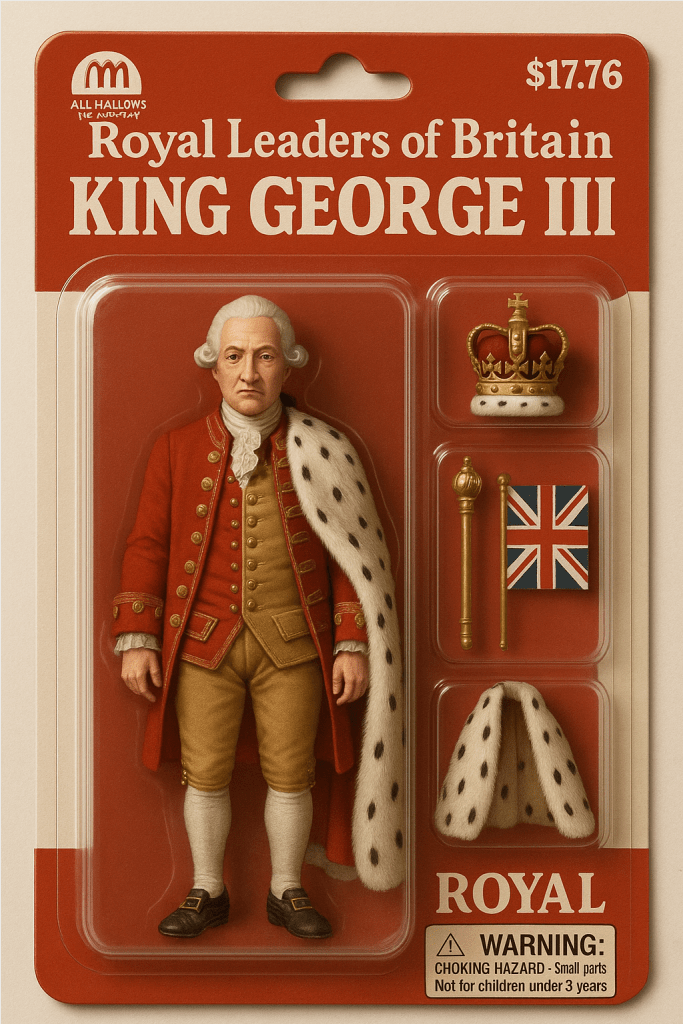

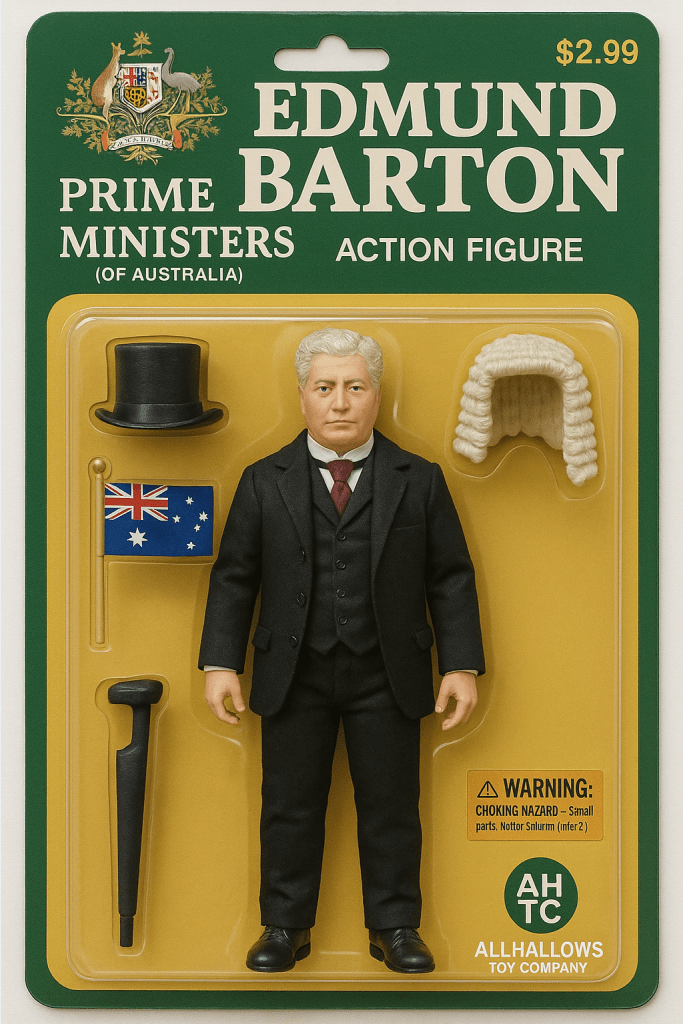

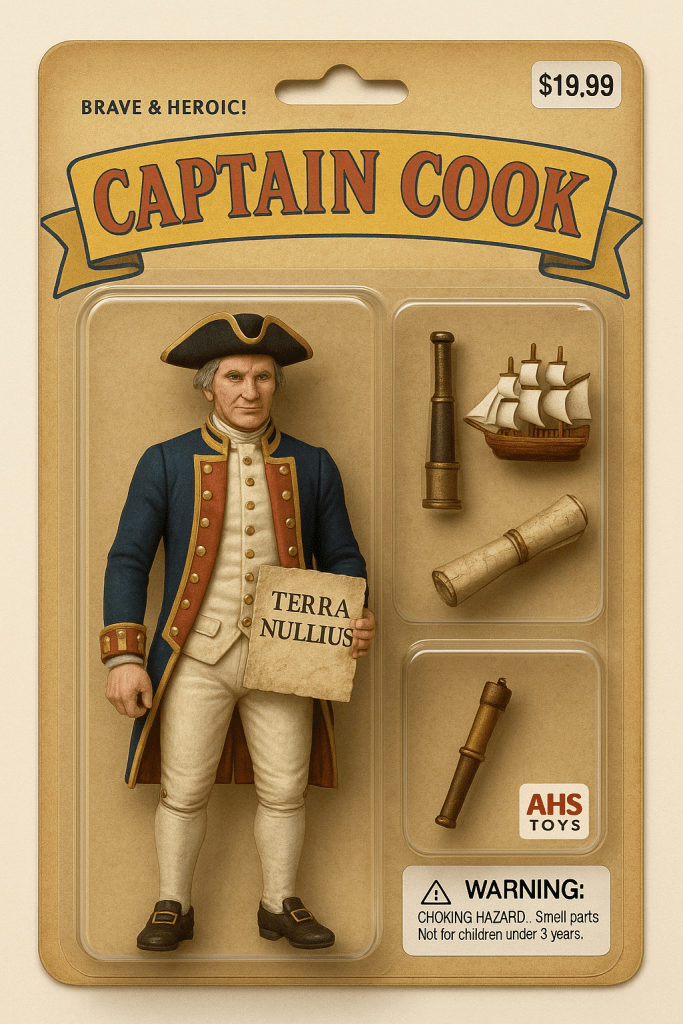

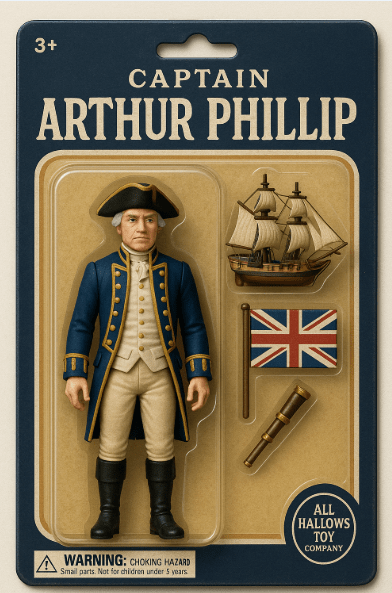

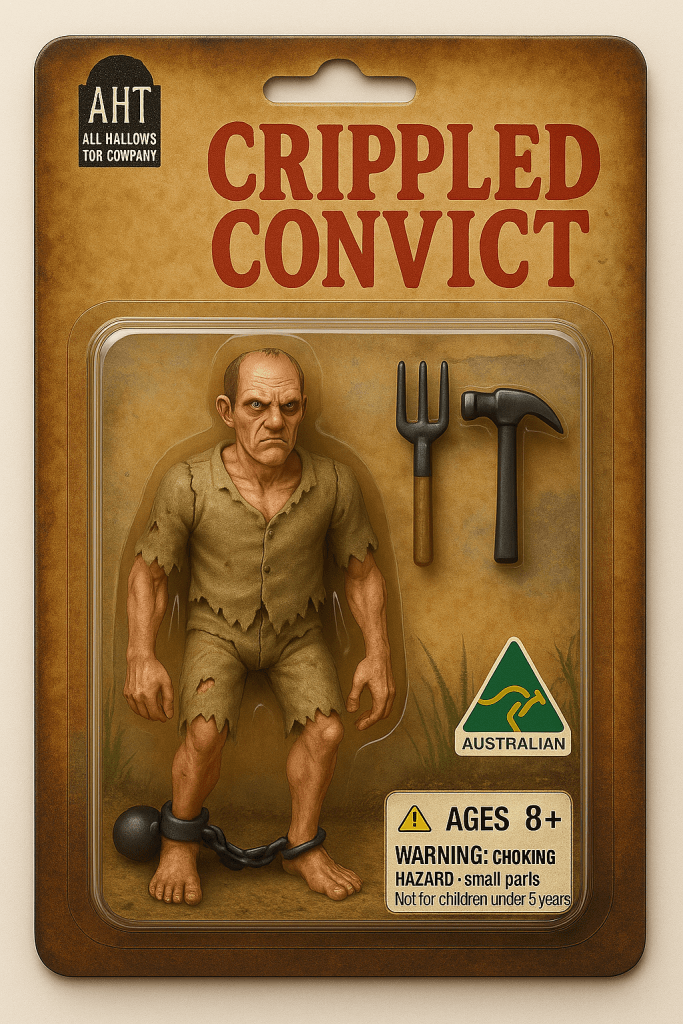

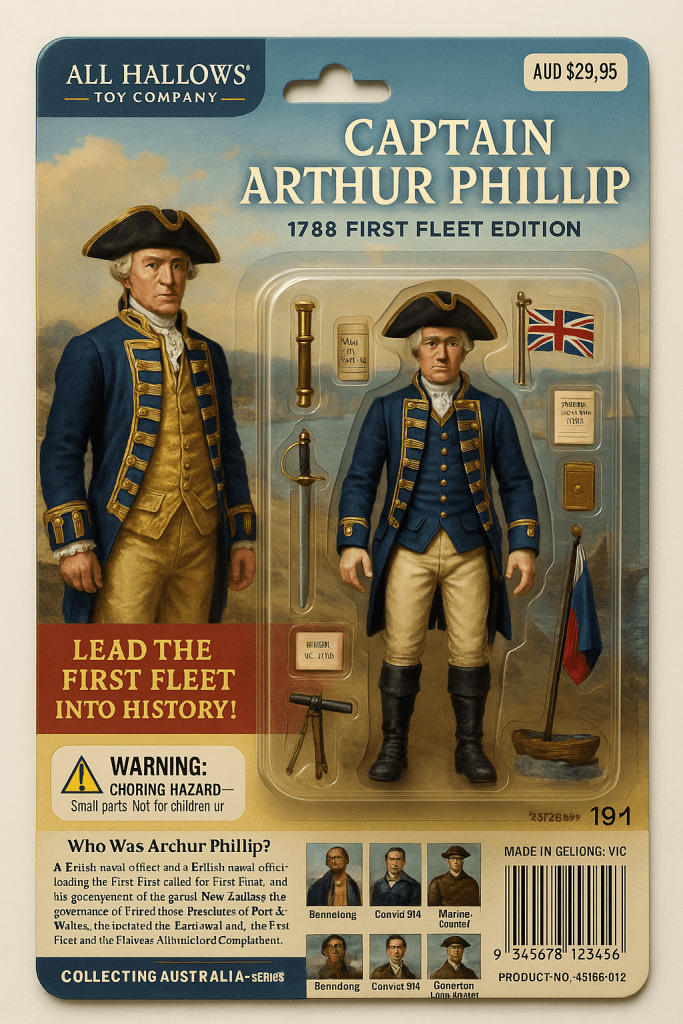

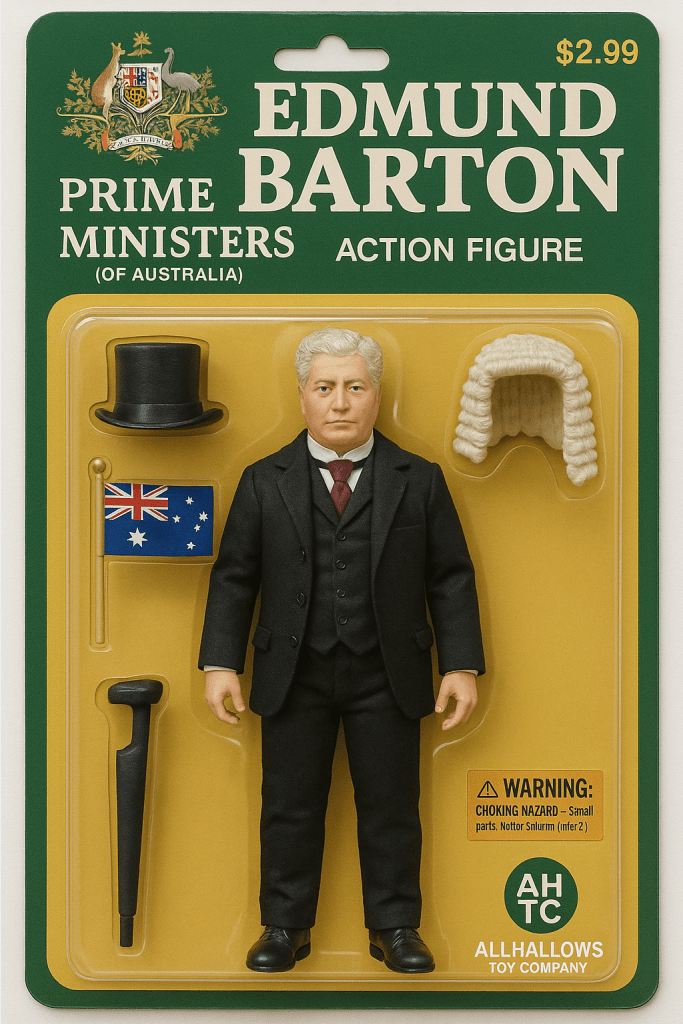

History Action Figures and the Politics of Representation

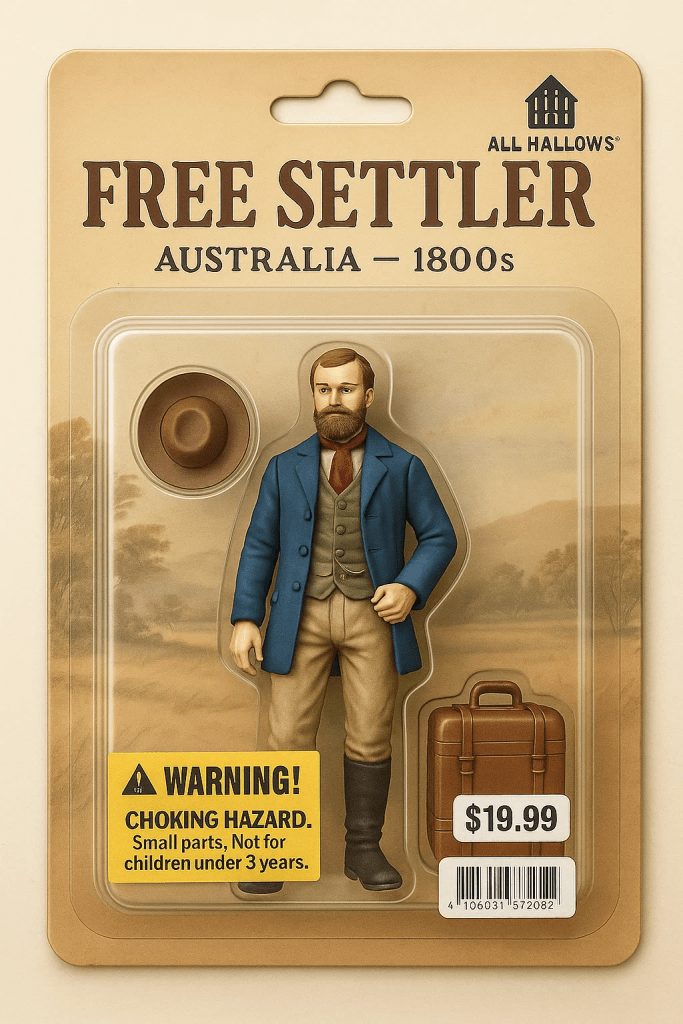

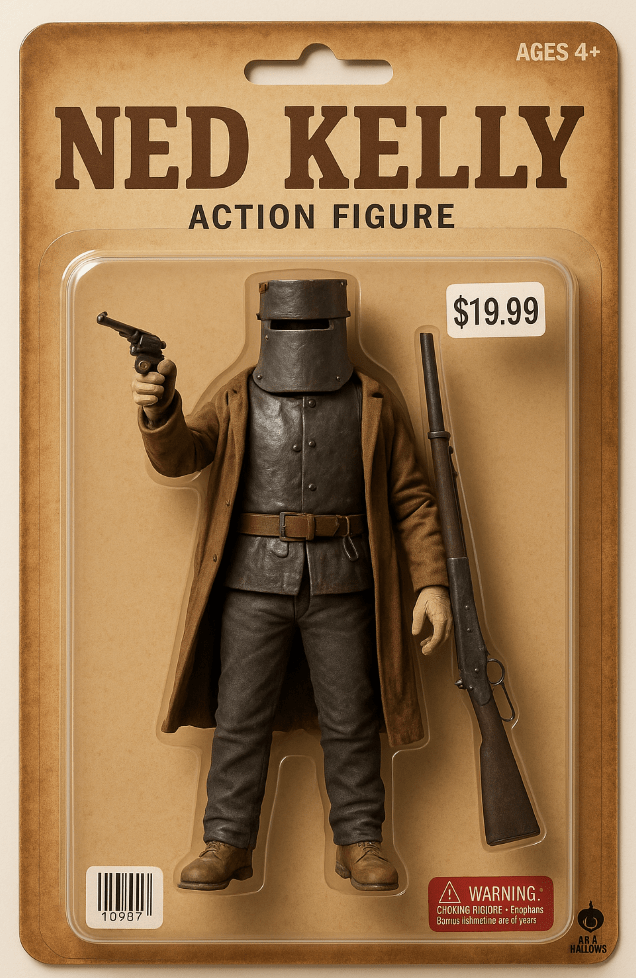

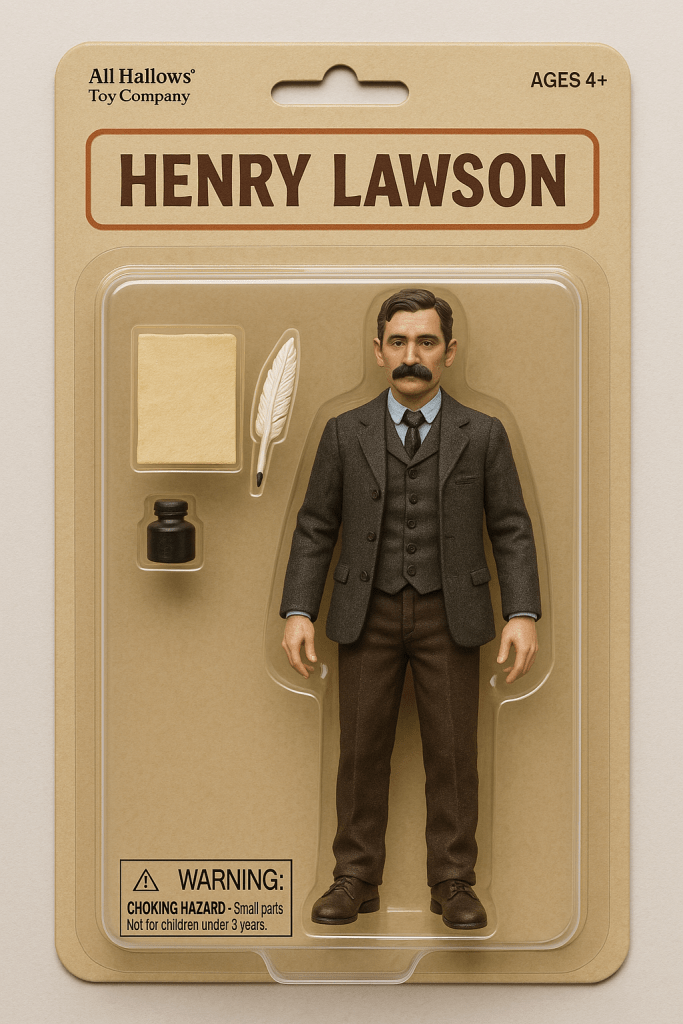

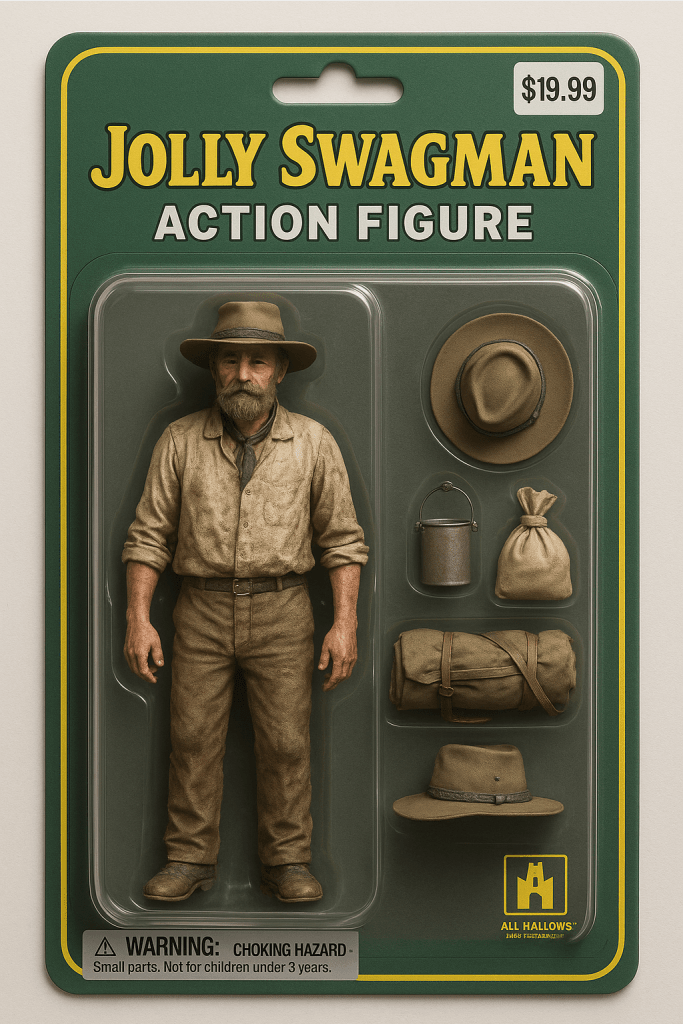

After confronting the narrow, celebratory narratives of Australia’s past using AI and NotebookLM, my Year 9s were ready for the next provocation.

We moved from text to toys.

The task? To create historically accurate action figures of the kinds of characters that appear in traditional nationalist histories of Australia — the kinds of stories students had just critiqued in the previous learning episodes. This activity extended the critique into a visual and material medium that helped surface how representation (and misrepresentation) operates even in something as seemingly innocuous as a toy.

Constructing a Whitewashed Past — One Figure at a Time

Students were invited to choose a figure from the traditional “pantheon” of Australian history:

- Captain James Cook

- Governor Arthur Phillip

- Convicts and Bushrangers

- Settlers and pastoralists

- King George III and Queen Victoria

- Prime Minister Edmund Barton

- Henry Lawson

- Even the “Jolly Swagman”

Using AI image generation tools, each student created an action figure toy (complete with historically appropriate accessories and packaging) for one of these figures.

The prompts were scaffolded using a range of historically accurate images and primary sources — RAG inputs that they had to research and justify.

Students were guided to use – and build upon – the 2 x “I” statement and a Verb approach to prompt writing during this activity.

What Emerged? A Landscape of White, Male Authority

What followed was a striking visual revelation.

The figures produced — regardless of who the students selected — almost universally reflected a white, male, Eurocentric authority. This wasn’t a glitch in the AI; it was a mirror to the dominant narrative that still underpins many popular conceptions of Australian history.

Students were quick to notice the deep seeded biases of the narrative.

By producing these figures themselves, the students were forced into a discomforting realisation: even when striving for historical accuracy, traditional stories offer an overwhelmingly narrow cast of characters.

That realisation wasn’t just intellectual. It was visually embodied.

This activity wasn’t about AI, fake plastic toys in algorithmically generated packaging. It was about perspectives and recognising the use of narratives to reinforce systems of power.

It echoed Sam Wineburg’s warning that the past is a foreign country — and one that has been repeatedly recolonised by familiar figures. It also reflects the way that classroom activities might unpack inequality and draw upon Cutrara’s call for a more aspirational and inclusive historical education — one that doesn’t centre settler heroes by default.

Future Steps: Toward Reparative Narratives

This sequence has become one of the most meaningful I’ve run. The use of AI here wasn’t just technical — it was tactical. It gave students tools to both replicate and disrupt dominant stories.

In our next engagement with this activity, students will develop counter-figures: action figures that challenge, reframe, and repair the omissions of the first round. Who might be represented if we rewrote our toy shelf of national memory?

It’s one thing to critique the stories we inherit.

It’s another to imagine what could be told instead.

The above activity was just the beginning.

In coming weeks, these students will be engaging in assignment work in the form of independent source analysis tasks. As they do so they will be called upon to consider histories that explore a range of perspectives.

Histories that challenge them to develop evidence supported reparative counter-narratives to the tradition notions of Australian history classrooms of the 1970s and earlier — historical retellings that centre a wider range of perspectives, agency, and resistance.

They’ll use the same tools, but this time to tell a different story: one grounded in justice, plurality, and complexity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.