Why explicit instruction and inquiry aren’t mutually exclusive

Last week, I travelled to Canberra for the HALT Summit – a professional learning experience that felt more like a reinvigorating recalibration than the ‘stock standard’ conference. Amid the powerful conversations about impact, innovation, brain science, leadership, and pedagogy, it was Nathaniel Swain’s keynote that had me thinking most deeply long after the applause of at the conclusion of the final had ended. Swain’s framing of ‘the science of learning’ was clear and evidence-informed, but what struck me most was the nuance: he offered fine discriminations that so often get lost in polarised dichotomous debate about effective pedagogy.

These finer discriminations and nuances helped conversations about ‘the science of learning’ sit more comfortably for me. It allowed me to reconcile the insights of Swain with my own lived experience. Interestingly, my takeaways sit comfortably with the observations of Cameron Paterson who, reflecting on a recent University of Melbourne lecture writes:

Science can explain how learning happens, but it doesn’t prescribe what or how we ought to teach; that depends on our values and context. [Emeritus Professor of the Learning Sciences Guy Claxton] warned against the “hegemony of narrow intellect,” which reduces learning to cold cognition and isolated elements. Real learning is an epistemic apprenticeship; we catch ways of thinking from the people around us. Culture matters. Exposition isn’t bad, but great teaching goes beyond delivery. It builds trust, fosters curiosity, and helps students learn how to think; not just what to know. The science doesn’t dictate action, it deepens our understanding and informs wise choices. *

At the HALT Summit, Swain explored why learning is “hard” and how teachers might teach in ways that make learning more accessible. He emphasised the need for teachers to reduce extraneous cognitive load on students while managing and optimising intrinsic load. He noted that cognitive load theory has its greatest application in contexts where students are novice learners. He explored student learning through the lens of biologically primary and secondary knowledge, and explored how great teaching facilitates student learning. He emphasised the value of checks of understanding (including contextually ‘safe’ cold calling, reviews and retrieval practice).

He articulated – perhaps better than anyone I’ve heard – that explicit instruction isn’t the opposite of inquiry. Swain’s presentation suggested to me that I have, perhaps, under-considered just how much explicit instruction, when thoughtfully applied, might be the the engine of effective critical inquiry in the history classroom. He emphasised that, despite its enormous impact and power in supporting learning, ‘how much’ explicit instruction is used in relation to other methodologies is very much context dependent. That context might include the age of students, the subject studied, the topic under consideration, the phase in the learning episode, the moment in the classroom, the experience and prior knowledge of the learner, and so on.

The keynote reminded me that much of what I do in my history classroom – modelling, checking for understanding, building knowledge sequentially – has deep roots. Rosenshine’s principles (published in 2012), that are prized by Swain, have been part of my teaching practice since my teacher training college days of the late 1980s, long before I had ever heard them named. Likewise, Swain’s work name check’s Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion. The approaches of both Rosenshine and Lemov are core to my teaching practice. they are a bedrock on which my pedagogical approaches are built. They are often unstated foundations of my flipped, AI-enhanced pedagogy for history. An approach that seeks not just knowledge transmission, but student agency and reparative historical understanding.

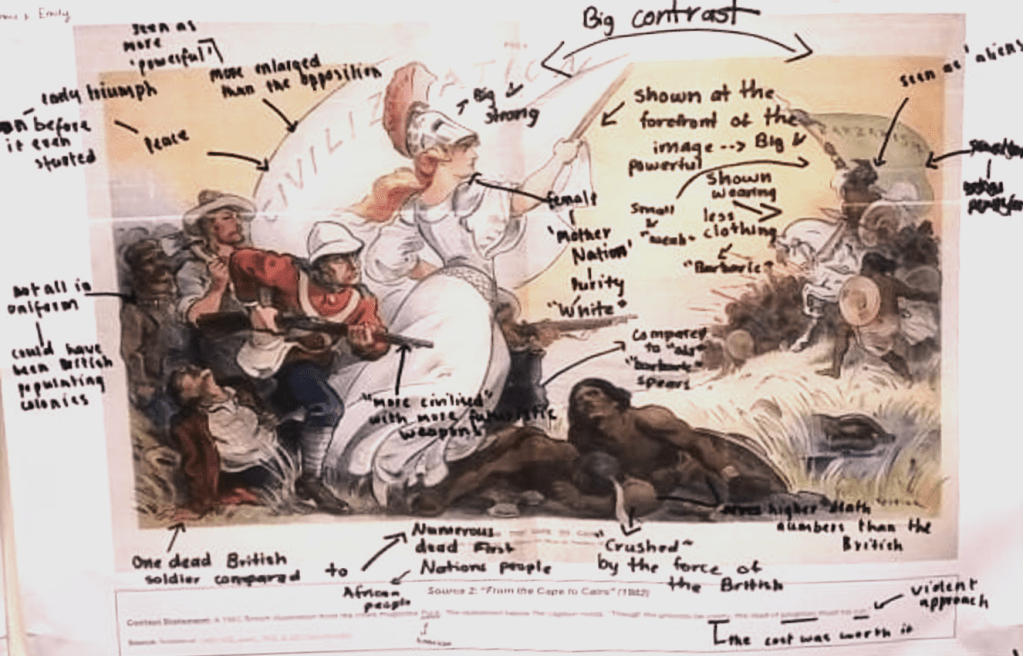

This past week in the classroom, I reflected on how those threads come together within my practice. This week, my students engaged with a range of primary sources – imperialist cartoons, antisemitic propaganda, and World War 1 photographs – through a scaffolded process that felt both disciplined and expansive. Some of these sources were extremely complex. Some replied on metaphor. All relied upon students’ grasp of strong grounding in historical knowledge.

Inquiry Begins With Grounding

In my flipped classroom, students begin their inquiry journeys with the development of content knowledge – not as static or unquestionable understandings, but as an intellectual grounding; a basis upon which more complex thinking can later be built. Through short pre-class videos, curated resources, and clearly organised class OneNotes and Teams classwork modules, students encounter the ‘facts’ of their topic, the contexts, and the core concepts that will later support the more challenging work of critical inquiry using historical sources. This provision of explicit instruction central to the “New Leaf” season in my termly seasonal structure – a time for orientation, context setting, vocabulary, and conceptual development.

Swain’s presentation helped me see the first phase of my unit cycle of learning more clearly. His emphasis on reducing cognitive load, establishing coherence, and modelling explicitly aligns with what I’ve long practiced – and what I saw affirmed this week in student thinking.

Establishing a substantial grounding of subject knowledge early in the unit empowers learning. Detailed content knowledge – what Swain would call “biologically secondary knowledge” – matters in history. When students, later in the learning cycle, are presented with historical sources to interpret, analyse and evaluate, they draw upon this knowledge. By doing so they are then able use skills to construct newer and deeper understandings – to make sense – more effectively. This effective learning is enabled or empowered because of their existing content understandings. On the basis of historical content understandings students are able to approach primary sources, including the pictorial sources my classes used this week, not as raw puzzles to solve, but as texts to interpret. Their abilities to detect multiple layered perspectives in an imperial map, to critique the antisemitic visual tropes in a 1919 Austrian cartoon, or question the narratives established through choices of imagery embedded in a battlefield photographs didn’t emerge spontaneously. It emerged because students had been equipped and empowered – with knowledge, routines, and teacher guidance. This knowledge, the routines, and the guidance were supported by a culture of learning.

Louka Parry, at the HALT Summit argued that such a culture supports student

- agency (where students move from “achiever mode” to “explorer mode”),

- belonging (where social connectedness is valued),

- curiousity (which must be both cultivated and proected)

- discernment (where questions of purpose and ‘what matters most’ are explored)

- “embodiment” (where students move within their space to collaborate, coteach, and codesign learning experiences).

At this point, I was interested to note that there are others who see the science of learning as a gateway into rich and deep learning that draws upon inquiry. One such voice is Jared Cooney Horvath – a neuroscientist, educator, and author. Pointing to the enormous impact of context upon how the science of learning might be applied in classrooms, Horvath notes:

“Traditional” educators commonly argue that techniques such as retrieval practice and spaced repetition work well in the classroom. In response, “progressive” educators commonly counter that inquiry and real-world application are required for deep learning to occur.

The astute reader will recognise that these debates rightly concern pedagogy; they are focused on “what works”.

It is at this point where both sides of the debate can (and should) meaningfully draw equally upon SoL as a source of evidence to support their arguments…

Teachers well versed in the science of learning are more likely to employ student-centered, constructivist approaches within the classroom that largely centre on agency and deep comprehension… **

A little bit of Rosenshine and Lemov… ?

For me, both the ideas of Swain and Parry are crucial. Ensure both aspects of learning are part of the history classroom doesn’t begin when the bell goes. It begins, both literally and metaphorically, before the door opens. This is where the ideas of Rosenshine and Lemov, in particular, are evident within my teaching of history. Their emphasis of structures and behaviour management routines shape the norms of working – the ‘rules of engagement’ – in my classroom. The norms provide for students a predictable learning context and classroom culture allow me to give certainty when the learning experience becomes less defined and less structured, when problems become more ill-defined. The norms of the room provide the psychological security and safety for students to take the risk of entering the unfamiliar and engaging what Parry called ‘explorer mode‘. This solid base is a launchpad, a springboard into more complex modes of learning

Students meet me outside the room – (generally loosely – as secondary students) lined up, older but still greeted outside the classroom and then cued in. Inside, they sit in structured seating arrangements that allow for clear teacher movement and close proximity. I’d like to think that the learning space is ordered, calm, and cared for.

These routines – so seemingly mundane – are part of what allows teaching to begin with focus. They take time and effort. They take daily maintenance. They form the foundational structure that underpins everything else.

Rosenshine’s work – long embedded in my practice – lives on in my flipped approach: reviewing prior learning, guiding practice, providing models, checking for understanding, ensuring challenge and success. These are not relics of a past pedagogy. They are the conditions that allow new pedagogies to thrive.

When students explore complexity – when they critique, compare, annotate, and question – they are not stepping outside of structure. They are stepping further into it. Flipped learning within a Deweyan inquiry model doesn’t replace explicit instruction. It repositions it. It gives me time to model. Time to listen. Time to respond.

And it gives students what Swain called “the cognitive conditions for learning.” Conditions that allow for thinking, yes – but also for care, for community, for curiosity, for exploration, for risk-taking, and for voice. For the courage to say, “Not only is this source is trying to tell me something but I have something to say back.”

Structure as a Springboard

While Parry rightly rejects ‘back to basics’ approaches as often little more than approaches that will drive learners and learning “back to mediocrity”, the structures often associated with such approaches can be powerful as ‘springboards’.

In class, we use familiar routines – for example, ADAMANT as a starting point for source analysis, routines from Harvard’s Project Zero, paired comparisons, and concept mapping – to guide our work. These tools aren’t rigid templates. They’re platforms. They give students the confidence to step into complexity without being overwhelmed by it.

One of the most important reminders Swain offered was that explicit instruction is not about “telling.” It’s about helping students attend to what matters. It’s about offering a model before inviting imitation, then individual interpretation. This week, I saw that dynamic unfold in small ways: students transferring knowledge from flipped videos to in-class source annotation and then to create their own new interpretations as the made sense of ideas within sources.

Swain’s view that frequent, embedded checks for understanding (CFU) are central to effective practice was visible throughout my teaching. Throughout the learning process, students weren’t just being assessed by being seen. These moments – spaced throughout lessons every few minutes – are grounded in the understanding that CFU is not a process separated from the learning process but an active and ongoing responsiveness – a “small a” formative assessment of understanding that is frequent in the classroom.

CFU is built into our class history source work: pairing students to talk, askin for responses from non-volunteers, and listening for thinking. Mini whiteboards are sometimes used. So are ‘warm’, scaffolded cold calls. These -the mechanics of my classroom management that supports pedagogy. They let me know when to echo, when to clarify, and when to reteach. As Swain put it, when done well, CFU isn’t “checking off” understanding. It’s shaping it.

Six core priorities from Swain

The embedded practices above reflect broader principles Swain laid out in his synthesis of the science of learning. His six core priorities are:

- Put student learning at the heart of teaching – by regularly checking for understanding and using retrieval to support memory.

- Make effective and engaging teaching the norm – not by entertaining, but by making participation possible and purposeful.

- Plan curriculum that is coherent, knowledge-rich, and includes regular review – through content sequencing in flipped videos and deliberate spiral returns to big ideas.

- Teach at the whole-class level responsively – using CFU to adjust in real time and to re-teach as needed without derailing momentum.

- Make it easy for students to participate – via clearly taught norms, movement routines, and predictable transitions between independent, paired, and group work.

- Invest in professional knowledge – including continuing to examine how emerging research (and emerging technologies such as AI) intersect with deep pedagogical wisdom.

These ideas aren’t add-ons. They are embedded – in how I teach, in how students learn, and in the culture of the classroom itself.

Why Swain Felt Different

What I appreciated most about Swain’s keynote at the HALT Summit was its refusal to flatten complexity.

Too often, the loudest voices in education frame things as binary: explicit instruction or inquiry; tradition or innovation. But Swain, in both tone and substance, disrupted that narrative.

He reminded us that guided practice is not “anti-agency,” that modelling is not “anti-constructivist,” and that knowledge-building is not the opposite of meaning-making.

This struck a chord, because so much of the recent pushback against inquiry seems to confuse it with discovery learning – as if asking students to grapply with ill-defined problems such as interpreting or analysing a historical source must mean that teachers are withholding all support, guidance, provision of a content-based context.

Historical inquiry, when done well, is a deeply scaffolded process of entering ‘explorer mode’. It is supported by substantial amounts of explicit instruction. It’s not a guessing game. It’s not free form, choose-your-own-adventure learning. It’s not a juvenile journey of discovery in which random holes are dug into a beach of information. It’s an expertly guided excavation into a site of learning.

Final Thoughts: The Work Ahead

If this week taught me anything, it’s that good history teaching is rarely either/or. It’s both/and. It’s explicit and exploratory. Structured and slow. Traditional and transformative. It deeply context based.

As we move further into the term, I’ll keep returning to the idea that agency isn’t something we hand to students. It’s something we help them build – lesson by lesson, question by question, scaffold by scaffold. That work takes time. And it takes grounding on knowledge.

Because before students can grow, they need something solid to grow from.

* Guy Claxton on the science of learning.

** Science of learning: what it really tells us about teaching | Tes

You must be logged in to post a comment.