In recent months, I’ve been reflecting on how to purposefully integrate Object-Based Learning (OBL) into my history classes. It strikes me that any fundamental shift in how we think about designing history pedagogy for the AI era should allow for increasing opportunities to engage with the physical world around them. I believe we should imagine AI, not as a replacement for human-centred learning but, as a space-maker.

It’s clear that AI, when well-employed, can take on some of the cognitive load of content delivery, automate routine tasks, and support differentiated pathways. When used within a flipped learning approach, it helps to make space for teachers and students to focus on the human collaborative and connection-making dimensions of historical learning that matter most.

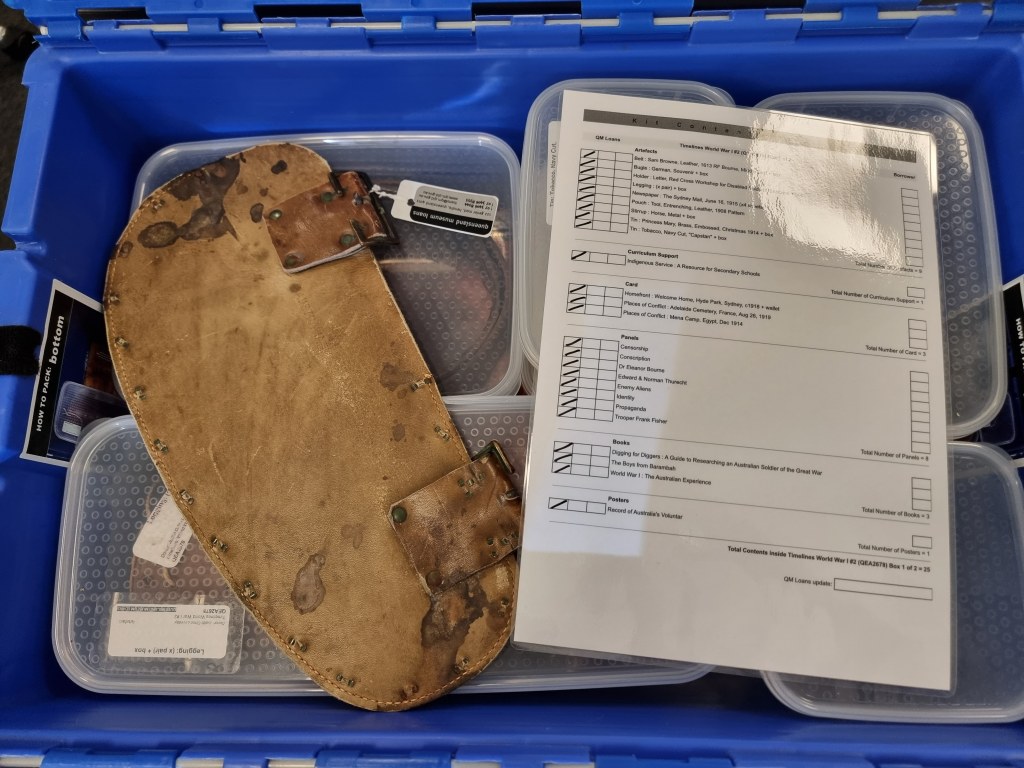

During the last week, in part inspired by the ideas of Nick Frigo (see The Power of Things: Object-based learning in the classroom) my students have had the opportunity to engage with some compelling historical artefacts – many borrowed from the Queensland Museum. I’ve done this type of lesson numerous times before… yet I have always felt something was missing in these lessons. I have always had this unquantifiable sense that my classes were not gaining from what I saw as an important learning experience as I had anticipated and hoped.

So it was that, with some trepidation, I again brought my students into physical contact again with the past through objects.

The objects were evocative.

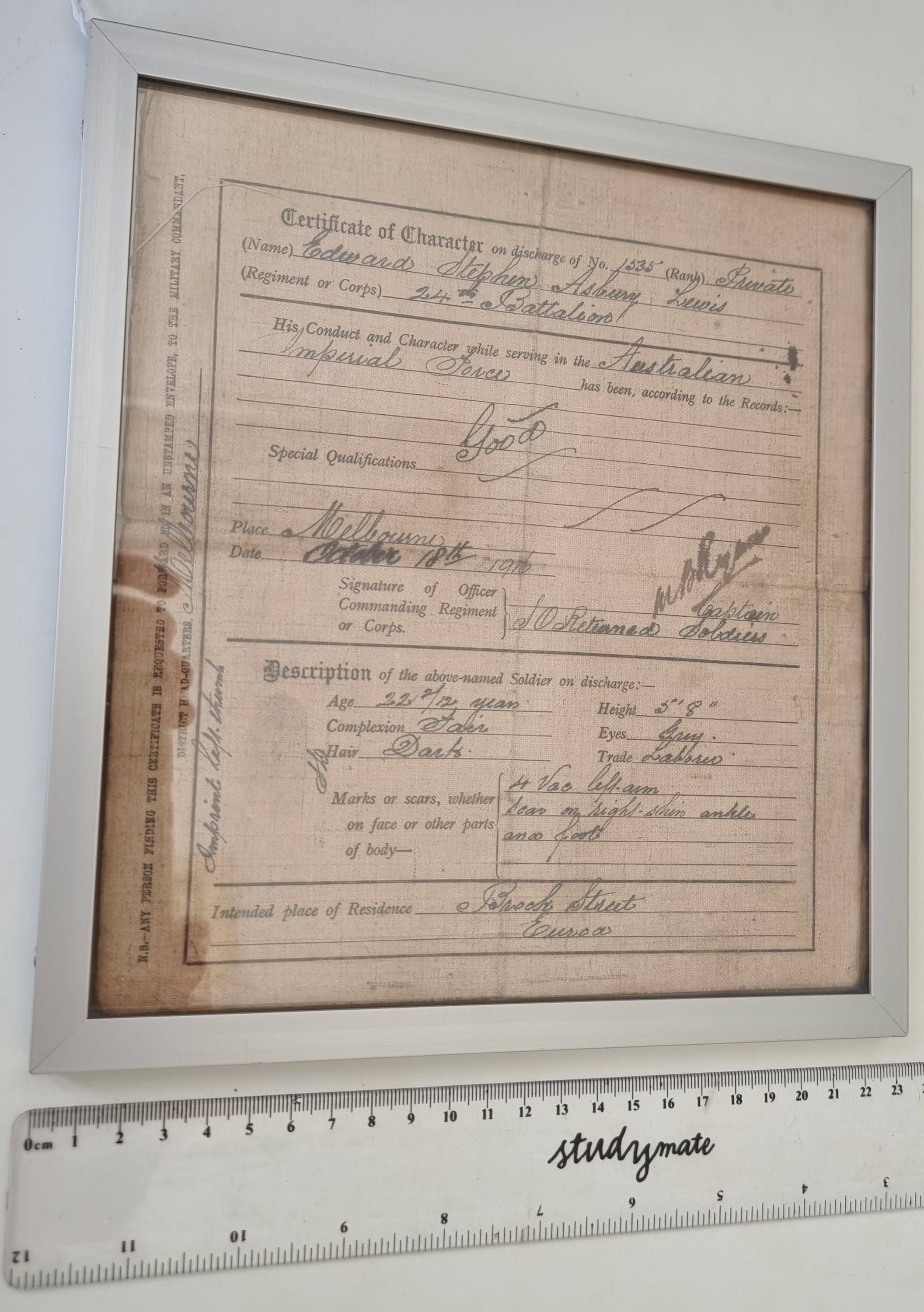

A Princess Mary gift tin from Christmas 1914; a soldier’s worn entrenching tool pouch; carefully preserved postcards and letters from soldiers home; trench art, badges and service medals, enlistment and demobilisation papers and more.

These objects are rich in texture, story, and emotional resonance.

I imagined they would naturally slow students down. I pictured them running their fingers along the tin’s dented edge, asking: Whose hands touched this? What did it carry? What did it mean? I wanted them to encounter the past not as a static set of facts, but as a living, human presence woven into the material world. I wanted them to feel a connection with the past.

But what I’m beginning to realise – and what my research is now helping me see more clearly – is that inviting students into deeper learning with objects, that building these slower, more reflective spaces requires more than simply putting interesting objects in front of them and asking them to complete a couple of quick exercises.

Reimagining History Pedagogy in the Age of AI

There’s a growing tension in education today. On the one hand, AI tools, flipped learning models, and adaptive technologies promise faster, more personalised, more efficient pathways for students to access knowledge. On the other hand, these same tools risk amplifying the pressures already compressing school life: the drive for more content coverage, more outputs, more measurable results.

Yet I believe there’s another possibility – one that frames AI not as a replacement for human-centred learning but as space-maker. Within a considered pedagogy, AI can take on some of the cognitive load of content delivery, automate routine tasks, and support differentiated pathways, leaving teachers and students with more space to focus on the human, ethical, and communal dimensions of historical learning that matter most.

For me, this is where Object-Based Learning comes into its own. OBL invites students to slow down, notice, reflect, and connect – with the past, with community, and with each other. It aligns beautifully with a slow teaching approach, one that resists the pace of “coverage” and focuses instead on depth, presence, and the cultivation of empathy and ethical awareness.

In a refreshed, AI-supported history pedagogy, I imagine the classroom becoming less a site of frantic content delivery and more a site of relational learning: a space where students encounter the richness of human experience, wrestle with complexity, and engage in collaborative, locally situated historical inquiry.

Designing for Presence: What Best Practice Looks Like

To move toward this vision, I’m beginning to develop layered, scaffolded OBL activities that invite students into slower, more intentional modes of historical inquiry. This is not about handing out objects and hoping ‘for the magic to happen’.

It’s about designing experiences that guide students to:

- Observe carefully – noticing materials, textures, marks of use, and small details they might otherwise skim past.

- Ask human-centred questions – not just what is this? but why did it matter?, who was connected to it?, and what does it reveal about lived experience?

- Build emotional and imaginative connection – through reflective writing, perspective-taking, and creative exercises that encourage empathy.

- Integrate object work into larger historical inquiries – connecting the material world to texts, archives, oral histories, digital sources, and ethical questions.

- Use AI tools as amplifiers, not replacements – supporting background research, extending connections, scaffolding personalised inquiry, and freeing classroom time for deeper, slower engagement.

Importantly, this work also connects students to community: local histories, intergenerational memories, community collections, and collaborative projects that root historical inquiry in shared, situated experience.

It’s also worth noting that, in the context of Object-Based Learning, an “object” refers to any material artefact – original, replica, image or digital representation – that carries traces of past human use, meaning, or experience and can serve as a focal point for inquiry, reflection, interpretation, and analysis.

Objects are not limited to rare or valuable items; they can include everyday tools, personal belongings, artworks, documents, textiles, or technological devices, each offering students a multisensory, embodied entry point into historical, cultural, and ethical questions.

The objects that can be engaged with are many, varied, and common.

Recognising the Common Traps

As I reflect on my own practice, I see familiar traps that I – and many others – can easily fall into.

One is the trap of novelty: using artefacts as entertaining props rather than grounding them in sustained inquiry. Another is under-scaffolding: assuming students know how to interpret objects or ask meaningful questions without enough structured guidance.

There’s also the pressure of time. OBL takes space – not just physical, but temporal space. Slow learning can feel like a luxury in systems focused on speed, assessments, and outputs. But this is precisely where AI, when used well, can help: freeing up time for the kinds of relational, reflective, human-centred work that machines cannot do.

Finally, there’s the challenge of teacher confidence. I am still learning how to balance open-ended exploration with clear frameworks, how to hold space for emotional engagement without overwhelming students, and how to integrate object work meaningfully with broader pedagogical goals.

Where I’m Heading Next

I am increasingly convinced that Object-Based Learning offers not just a teaching strategy, but another window into how we may imagine history pedagogy for the AI era.

In this vision, the classroom becomes a space where students and teachers together create moments of presence – slowing down to sit with the ethical, emotional, and human dimensions of history. It’s a classroom where technology amplifies possibility but does not crowd out presence; where rich connections to global narratives can be fostered; where students build not just knowledge and skill, but empathy, imagination, voice and agency.