If you’ve followed this blog for a while, you know I don’t believe doing things – including excursions or field trips – just for the sake of ticking a curriculum box or burning up a bus budget. Teachers need to act with purpose. They must know their why. To me our purpose is clear. We are about learning. Therefore, class activities must be about learning – not about filling in time, not just about ‘engagement’, and not ‘just fun’.

School excursions – when designed intentionally – can become a cornerstone of a technology-infused, transformative history pedagogy. They disrupt the rhythms of classroom life, open up space for student agency, and remind us that history is not just something to study but something to do. They offer opportunities for connection, collaboration, and creativity that are often beyond what’s possible within a normal classroom. They offer a way for our students to engage with community. They are important and powerful interruptions to the school routine. They deserve attention to design, execution, and follow-up.

And let’s not forget that last bit: The real magic doesn’t happen only when on the site of the excursion. It happens when we return to the classroom, when we slow down, and when we create moments of sense-making.

The Magic Doesn’t Just Happen: Scoping the Space Beforehand

Before any student sets foot on a field trip, I’ve been there. Alone or with a colleague, I walk the site, check the flow of space, test the signage, online information, guide materials and maps, observe the sensory experience, and mentally map out where learning moments can emerge. I note the facilities and the hazards. A pre-visit is crucial if we are to truly a consider the needs of our students. Whether it’s the haunting stillness of Toowong Cemetery, the solemn geometry of Brisbane’s Anzac Square, the layered wartime narratives at the MacArthur Museum, or the powerful presence of Fiona Foley’s Witnessing to Silence installation, every site demands careful, intentional preparation.

A successful excursion isn’t just about showing up on the day. It’s about showing up prepared – not just with risk assessments and transport plans (though yes, those too), but with a vision for how students will interact, inquire, and make meaning on site.

Designing Presence… and Using Tech!

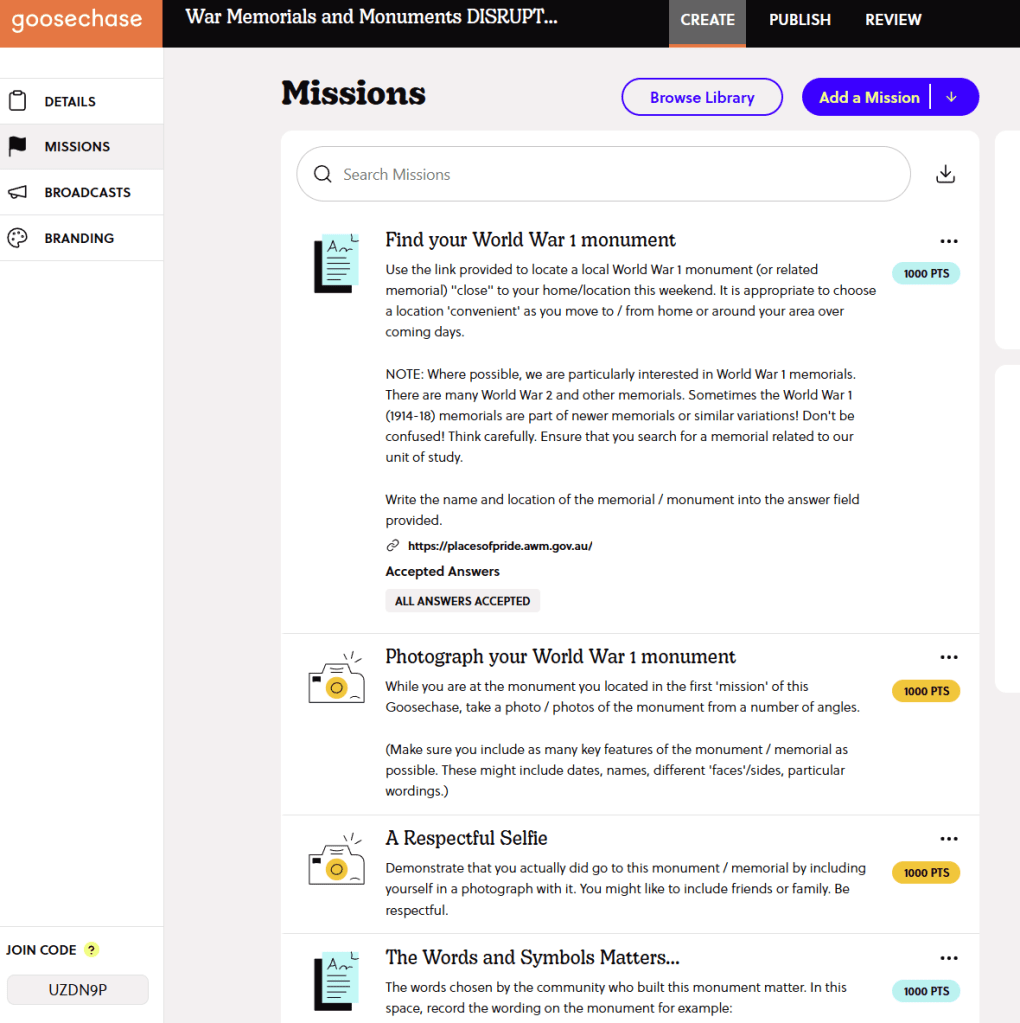

In one of my blog earlier posts, I wrote about how the GooseChase app has reshaped how I approach excursions. At Anzac Square, for example, we’ve used GooseChase to create scavenger hunt-style missions of engagement that go far beyond trivia. Students guide themselves, examine memorials, interact with guides, photograph details, and reflect on the histories – and silences – embedded in the space. They sometimes stop – pause – to take stock – to drink in the moment for what it is.

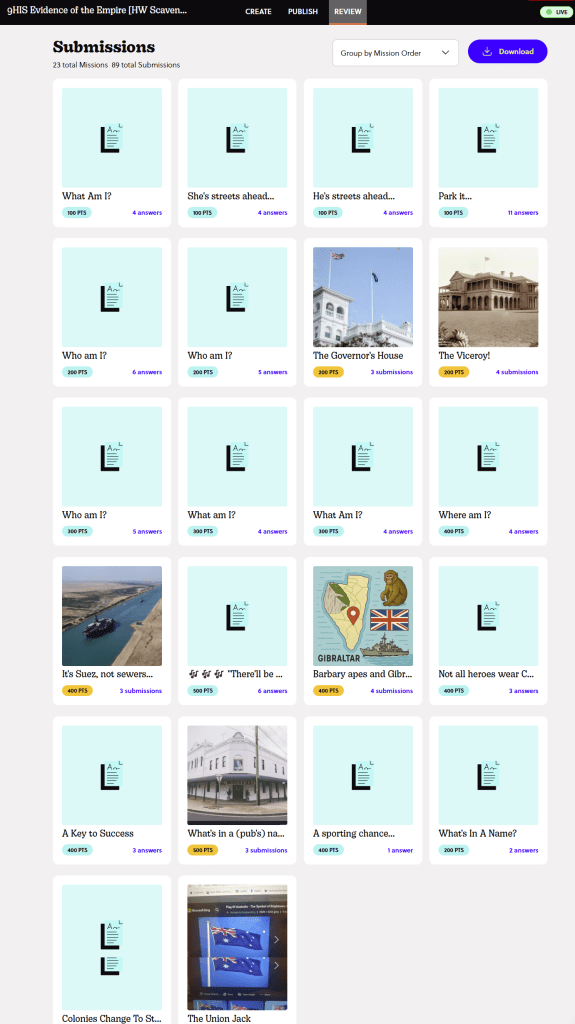

I now use the GooseChase app on all my excursions and field trips, and its impact has been nothing short of transformative. What perhaps began its life in the minds of its designers as a tool for playful scavenger hunts has become, in my practice, a means for me to scaffold for deep presence, inquiry, and connection. GooseChase allows students to move beyond passive observation and constant teacher direction. The students have autnomy: they interact with the space, engage collaboratively, record insights in real time, and surface their own interpretations. Importantly, the app democratises the experience — guides and teachers are not required to be ‘sages on stages’, students are not required to stand or sit in silence as they are lectured while a rich experience surrounds them. Further, with some simple planning, students without smartphones can participate fully in team missions, and every group’s voice is amplified when we debrief back in the classroom.

Again and again, I’ve seen GooseChase draw out reflections and observations that would never have emerged from scrawled beetle-scratchings of notes on a crumpled worksheet on a clipboard: students using the app can be positioned to grapple with silences, notice marginalised stories, or make personal, meaningful connections to the past. For me, GooseChase isn’t an optional tech add-on; it’s a core part of how I design field experiences that foster agency, presence, and historical thinking.

More recently, I’ve added another layer: Polycam, a 3D Lidar scanning app used via a set of iPads. With Polycam, students use cutting edge technology to create detailed, manipulable 3D models of monuments and artefacts. Suddenly, they’re not just looking at the past — they’re documenting it, capturing its spatial and material reality, and bringing it back into the classroom for collaborative analysis. These models can then be uploaded and labelled in platforms like Thinglink, where students create interactive, annotated digital artefacts layered with historical context, personal reflections, and multimedia connections. This process lets students become curators as well as investigators, surfacing marginalised stories and linking objects to broader historical themes. In some cases, we even 3D print the models, adding a tangible, hands-on element that deepens engagement and brings the learning experience quite literally into students’ hands.

One of the most powerful examples was when my students scanned and 3D printed the suffragist Emma Miller’s grave marker at Toowong Cemetery, creating a classroom artefact that sparked discussions on gender, activism, and historical memory. They also scanned a range of other Toowong sites, including the grave of Samuel Walker Griffith, a foundational figure in Queensland’s political history. Beyond the cemetery, they captured the marker at the site of resistance leader Dundalli’s execution in Brisbane’s Post Office Square, opening space for critical conversations about Indigenous resistance, colonial violence, and public memory. In Brisbane’s Anzac Park, students scanned a variety of war monuments (including a monument to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Service and the service of Women During World War 2), using both the digital Thinglink-annotated models and physical 3D prints to deepen their commemorative inquiries. These projects don’t just bring history into the classroom — they put it directly into students’ hands, empowering them to become active participants in meaning-making and historical interpretation.

Excursions as Slow History

Excursions fit beautifully within what I’ve called a “slow teaching” approach to history. We live in a hyper-speed, content-packed world, where even students’ emotional and cognitive spaces are increasingly fragmented. But history resists that. History, when taught well, slows us down. It invites students to linger over questions, wrestle with complexity, to make connections, and sit with ambiguity.

On an excursion, that slowing down happens almost naturally. The sheer physicality of being present in a place – sketching, recording, scanning, reflecting – interrupts the rush of the everyday. It demands attention, presence, and care.

What Comes Next… “Not Just Going Somewhere”

But here’s where many teachers miss a vital opportunity: what happens after the excursion?

When we return to the classroom, we have a choice. We can file the permission slips, tick off the risk assessment forms, and move on to the next lesson. Or we can slow down and revisit the experience, deliberately making space for sense-making.

In my own practice, I’ve found that creating a post-excursion reflective space — sometimes using the GooseChase photo submissions, sometimes through student-annotations of 3D scans, sometimes with collaborative slideshows, sometimes through the use of Harvard Project Zero thinking routines — transforms the excursion from a standalone event into an integrated, meaning-making experience. Something the enriches learning.

This is where students connect the dots:

- What did we experience that changed how we see this topic?

- What experiences or stories stood out, and why?

- How did the physicality of place shape our understanding?

- What tensions or silences did we notice?

How might we act differently – as learners, as citizens – because of what we encountered?

These conversations, grounded in reflection, are where transformative, reparative, generative history pedagogy takes root. This is where we move from the surface level of “going somewhere” and “doing something” to the deeper level of “becoming someone” – someone more attuned to justice, memory, complexity, and possibility.

Listening to Country: First Nations Stories and Spaces

It’s important to remember when conducting field trips and excursions in Australia, that we walk an ancient space. Every place in Australian history carries a story – and it’s essential to recognise the cultural and spiritual significance of place, especially when we teach on stolen land. For non-Indigenous students (and teachers), engaging with the idea that Country is alive, storied, and deeply connected to identity is a vital part of learning.

Places don’t just tell stories overtly or in words; they speak through positioning, through silences, and through what is left out. A cemetery, an Anzac memorial, a government building – all can open conversations about enduring connections to place, the way some narratives are privileged over others, and the unfinished challenges of justice, recognition, and truth-telling.

In my own practice, we engage with First Nations history and perspectives in tangible, site-based ways. Museums are increasingly intentional about embedding First Nations stories in their exhibitions, and the Australian Curriculum’s cross-curricular priorities ensure that Indigenous perspectives should be woven into our teaching. At Anzac Square, for example, we’ve laid an Australian floral wreath not only to honour those who fought in global conflicts but also to remember those who fought, suffered, and died in the Frontier Wars.

Beyond formal memorials, we work to acknowledge and foreground the First Nations place names, languages, and histories that surround us. They’ve always been there — waiting to be acknowledged, waiting to be heard. Every road, every pathway, every bird song and tree carries a story. The challenge is to listen.

As teachers in Queensland, we don’t take on this work alone. We consult with local First Nations communities, cultural centres, Elders, and organisations — including the Queensland Museum, the Anzac Square Learning Centre, the State Library of Queensland, and the many community leaders who generously share their expertise. These partnerships are essential to ensuring that the excursions we design are respectful, authentic, and culturally responsive.

Designing for Disruption, Designing for Agency

Excursions, when designed well, are not add-ons or rewards. They are disruptions – planned, thoughtful interruptions of classroom rhythms that create space for new forms of inquiry, connection, and agency. They are a chance to let students be present to place, history, and each other.

But the key is what comes next. When we return to the classroom, we owe it to our students to make space for revisiting, rethinking, and reweaving those experiences into the larger tapestry of their learning. It’s in this reflective, collaborative aftermath that excursions move from being “just a trip” to becoming a pivotal moment in students’ civic, global, and personal development.

In other words: the bus ride back is not the end of the learning. It’s the beginning of something more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.