There are a LOT of AI generated action figures – complete with packaging -being shared online at the moment. We’ve seen this kind of behaviour before from GenAI users but this time, the craze got me thinking more deeply.

Like many, I’ve seen many in my professional LinkedIn feed as teachers, educators, consultants, and tech-types have followed the craze. I’ve even seen quite a few from family members who have created their own little fun representations of themselves in a variety of costumes.

Certainly, the ability to add our own facial figures to prompts has been a powerful way of reinvigorating the image generation experience for many users of Generative AI. Suddenly, action figures are everywhere.

Why are we – and our students – so drawn to AI-generated action figures, stylised Funko Pop dolls, and similar toy-style renderings?

Perhaps it reflects our childhood desires for our toys to take on lives of their own? Perhaps it’s an indication of how much we were willing to transfer our personalities onto inanimate objects – our toys – as we played as children? Perhaps the creation of these images are a mashup of nostalgia, novelty, and aesthetic control? Perhaps it’s the appeal of turning powerful memories stories into collectible, bite-sized icons… and then sharing these with family, friends, colleagues and connections in a sense of online communal experience? A grown up ‘show-and-tell’ moment? Perhaps the reason is best left for a study by a psychologist?

For me a more important question for educators is: ‘How might this popularity be remixed and transformed into meaningful learning experiences for students?’

In the History classroom, these tools open new space to interrogate historical memory, iconography, and the ethics of representation. When used thoughtfully, these creations become more than just playful diversions – they become provocations for critical thinking, visual literacy, and ethical engagement.

This post explores how slow, deliberate teaching practices – grounded in inquiry and scaffolded by structured prompt-writing routines – can transform the use of AI image generation from a gimmick into a powerful tool for historical inquiry.

What Are These Things? And Why Make Them?

AI-generated action figures are stylised digital illustrations that can be used to reimagine ourselves and others – including historical figures – as miniatures, a dolls, as action figures, as collectible toys.

Essentially, these tools are created using text-to-image AI tools like those in OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, and others such as Midjourney.

Type in a suitably detailed prompt – describing everything from clothing to facial expression to background design – and the AI generates an image accordingly. If you want to you can even upload an image of the subject for your to guide the generation. (Of course, be conscious of ethical considerations around this!)

There’s an obvious surface appeal: they’re novel, eye-catching, and sometimes slightly absurd. To me, sometimes they are best described as amusing cultural artefacts – remixing nostalgia and digital creativity – that may unwittingly reveal their creator’s biases and sense of self-identity…

But when these images are introduced into the context of a History classroom, they may well be able to take on new dimensions.

They might prompt us to ask:

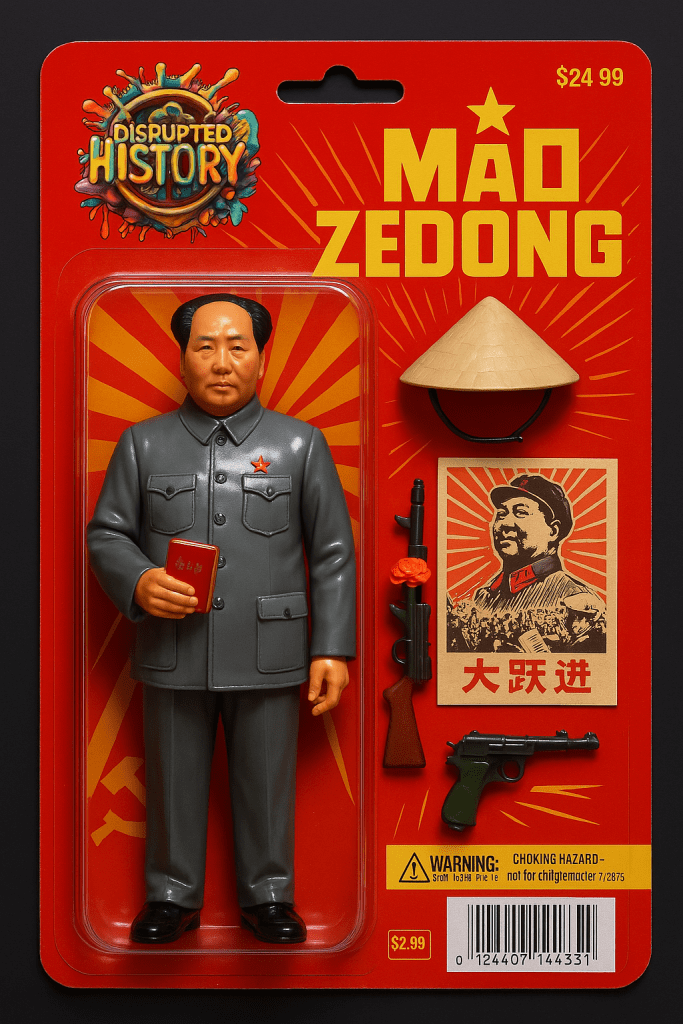

- Who do we choose to render and remember? Who do we overlook?

- How do we choose to portray those that we choose? What does this reveal about that character? What does it reveal about ourselves?

- What does it mean to render history in toy form?

- What part do toys – and other forms of popular culture – play in the creation, shaping, and transmission of historical memory?

- Where is the line between simplification, exaggeration, emphasis, symbolic representation and distortion? Between information, misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda?

The Pedagogical Potential: More Than Just a Gimmick

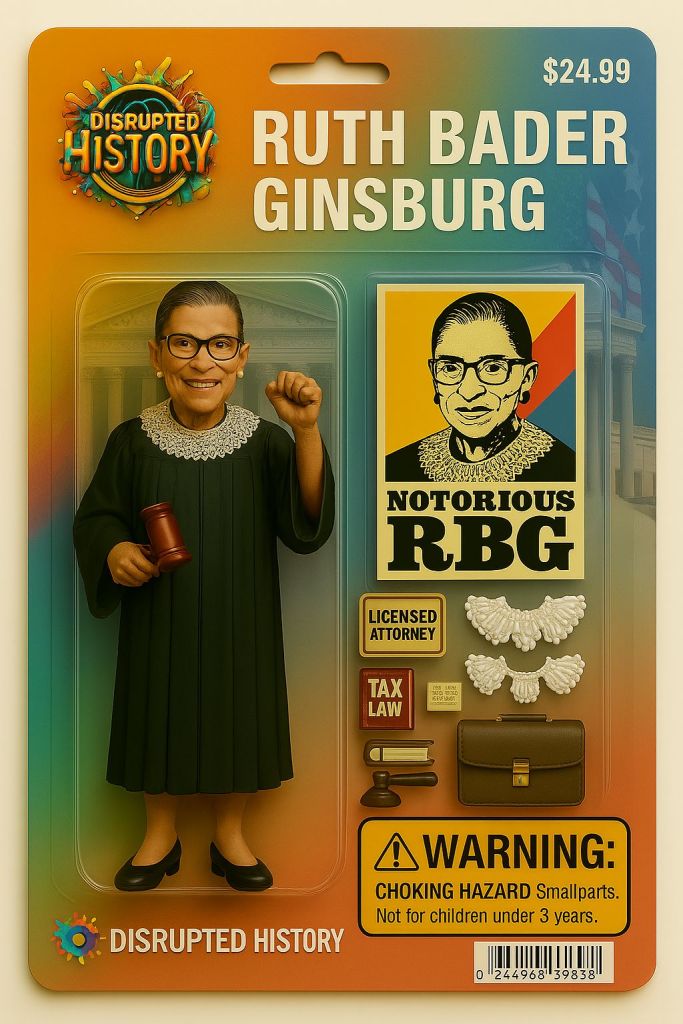

Used with care, AI-generated historical toys can be an innovative lens through which students explore:

- Historical interpretation and analysis (What are we emphasising? What do the sources emphasise? Whose perspectives are privileged?)

- Source evidence (What are we basing this on? What is the reliability of these sources?)

- Representation and bias (What’s missing? What are the limitations of our sources?)

- Visual rhetoric (What meanings are constructed through visual design? How is this meaning transmitted to an audience?)

Rather than treating these images as endpoints, teachers can position them as provocations – opportunities to slow down, unpack, and discuss the many choices (and silences) embedded within them.

This is where slow teaching comes in.

Rather than rushing to the image generation, we can build conceptual scaffolds. We can pause. We can reflect. We teach the thinking behind the creation.

Students can examine not only what’s on the screen, but how it got there – and what it means. They can generalise from this experience into other aspects of their lives.

Scaffolding Student Prompt Work: I-Statements, Iteration, and Plussy Practice

In my own practice, I’ve developed a structured method for helping students – as often novice users – to craft thoughtful, evidence-informed AI prompts. These ideas are explored elsewhere in this blog. The core of this method involves three elements:

- The “I-Statements and Verb” Framework

Students begin with (at least) two “I” statements that clarify perspective, intention, or empathy (e.g., I want to show…, I believe this figure is important because…), followed by a verb that anchors the purpose of the prompt (e.g., to commemorate, to investigate, to visualise). This grounds the work in historical thinking. - The “Plus-3 Iterations” Routine

Students generate an initial prompt and then refine it over at least three iterations of multi-turn chat dialogue with AI. With each cycle, they might evaluate the results, clarify meaning, challenge responses, adjust tone, or revise for historical accuracy. This multi-turn conversation helps them develop metacognitive awareness of prompt construction and evidence use. - “Plussy” Referencing

The term “Plussy” refers to the practice of attaching reference documents, images, or artefacts to support or guide the AI response. This mirrors the “+” function in ChatGPT or Copilot, or the paperclip function in Gemini. It transforms the AI from a generic responder into a source-aware assistant. By incorporating RAG-style materials – such as primary source packets, historiographical summaries, or class notes – students exercise control over the direction of their AI generated responses to help ensure that their generated results are grounded in historical context and research, not fantasy.

Together, these three layers cultivate responsible use of AI and a deeper understanding of the interpretive work that underpins historical representation.

Not Just How But Should We? Cultural Protocols and Ethical Limits

Always keep in mind that teaching with AI is a process that needs to bring humanity into the loop! Creating AI-generated images of historical personalities is making AI-images of real people! The process is one that demands respect. It demands critical thinking, deep knowledge and understanding, humility and ethical reflection.

For example, while exploring possible figures to create, I noted the existing online and historical bias towards representing the stories of European, able-bodied men. Initially, I considered an attempt to rebalance this representation by making an image of Vincent Lingiari, a central figure in Australia’s land rights movement. However, I chose not to proceed out of respect for cultural protocols around the depiction of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This process of decision-making represents an opportunity for a valuable ‘teachable moment’ in classrooms.

Ethical engagement with AI doesn’t stop at copyright. It extends to cultural knowledge, identity, and historical justice. Students must be invited into this complexity – grappling with questions like:

- Who has the right to represent whom?

- What does responsible digital storytelling and ethical representation look like?

- Where might AI tools reproduce harmful simplifications or erasures? Where might they be used to correct such harms?

These are not side notes. They are central to the work of history education in the AI age.

Scenarios for Classroom Use

1. Repackaging the Past

After studying a unit (e.g. suffrage, civil rights, revolutions), students might design an action figure. But before generating anything, they must:

- Choose and justify their choice of figure

- Select three key visual details, each backed by source evidence

- Draft a “packaging blurb” as a historical summary

This activity could be used as a a check for understanding of students’ ability to interpret, analyse, evaluate, synthesise, make ethical decisions, and create using digital tools. In essence this activity could provide an important experience of not only historical literacy but also digital literacy and citizenship.

2. Source-Based Prompt Writing

Provide a set of primary sources (photos, letters, speeches).

Ask students to write a historically accurate image prompt that reflects those sources. This bridges the gap between document analysis and creative production.

Students might even conduct their own research to identify reliable historical sources to draw upon to create their own prompts and images.

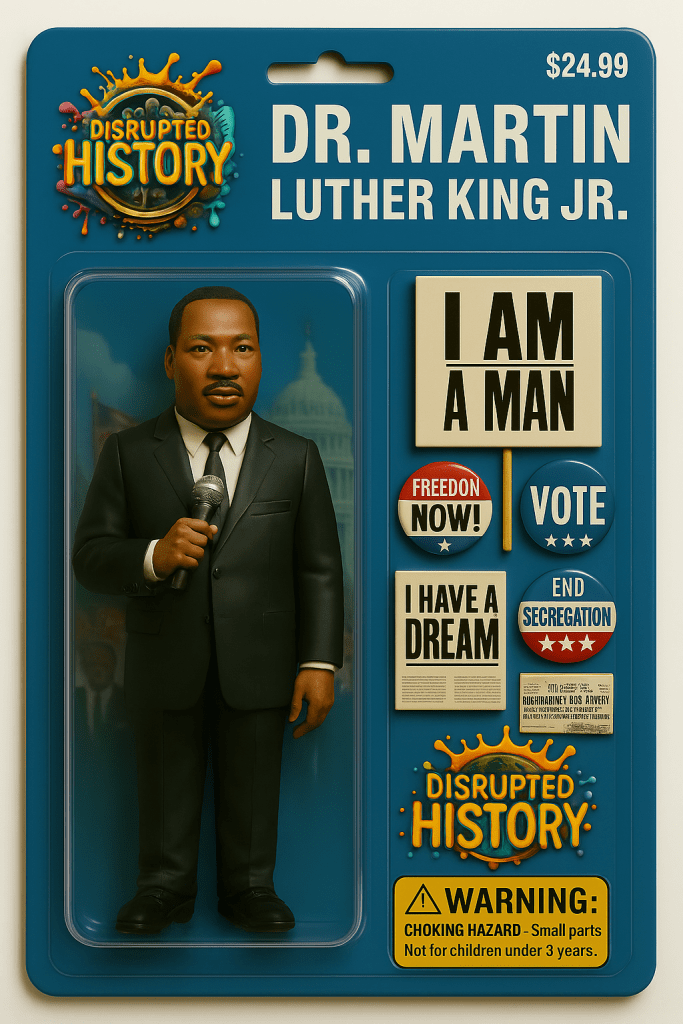

3. Counter-stereotyping the Historical Canon

Ask: Who isn’t usually turned into a toy?

Challenge students to find often overlooked figures, groups and communities – perhaps women, children, Indigenous leaders, working-class activists – and give them the visual spotlight.

This raises discussions about historical significance, silencing, perspectives, representations, and bias.

It raises questions of how historical learning can be both generative and reparative.

4. Historical Perspective and Audience

Use multiple AI-generated figures of the same person to discuss how history is remembered and constructed.

Students might design a variety of action figure prompts of the same historical figure – to create different characterisations in the form of a toy for different audiences. How might representation change for a national audience? An international audience? Close supporters? Opponents? Family and friends? For a group affected by the figure’s actions?

What changes? What remains the same? What does this tell us about perspectives?

Compare the different interpretations and ask students to evaluate accuracy and symbolism.

Try these prompts and activities

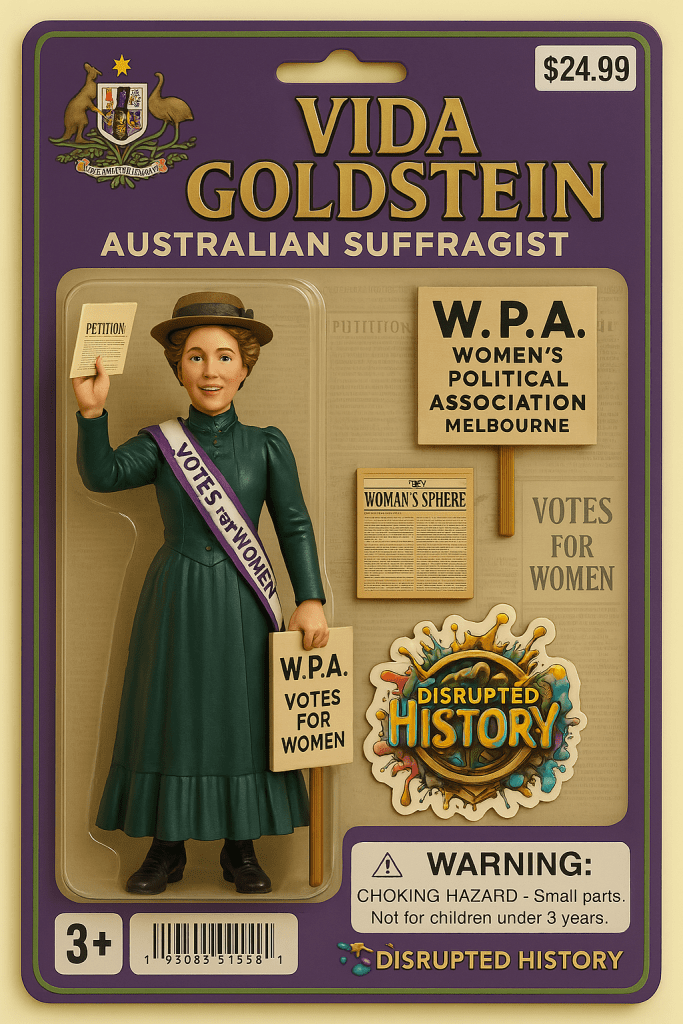

Create a suffragist Vida Goldstein figurine.

I am a teacher experimenting with the potential for historical learning in the creation of AI-generated action figures. I am interested in the ways colour, symbols, words, and other elements of design in toys might shape historical representations. Create a historically accurate action figure of Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein in lifelike colour. She wears early 20th-century Edwardian dress with a suffrage sash reading ‘Votes for Women.’ The figure is posed as if giving a speech. Include modern vibrant toy packaging with Australian federation symbols, purple-green-white colour palette, and archival newspaper clippings in the background. The action figure doll must be full body length and in “3 dimensional” plastic as if a real children’s toy. It must include accessory toy parts and pieces such as newspapers and signs related to her life an work as a suffragist with the WPA and newspaper The Women’s Sphere. Include realistic product packaging details including price, barcode, safety warnings and so on.

My prompt and the related multi-turn chat thread in ChatGPT is accessible here.

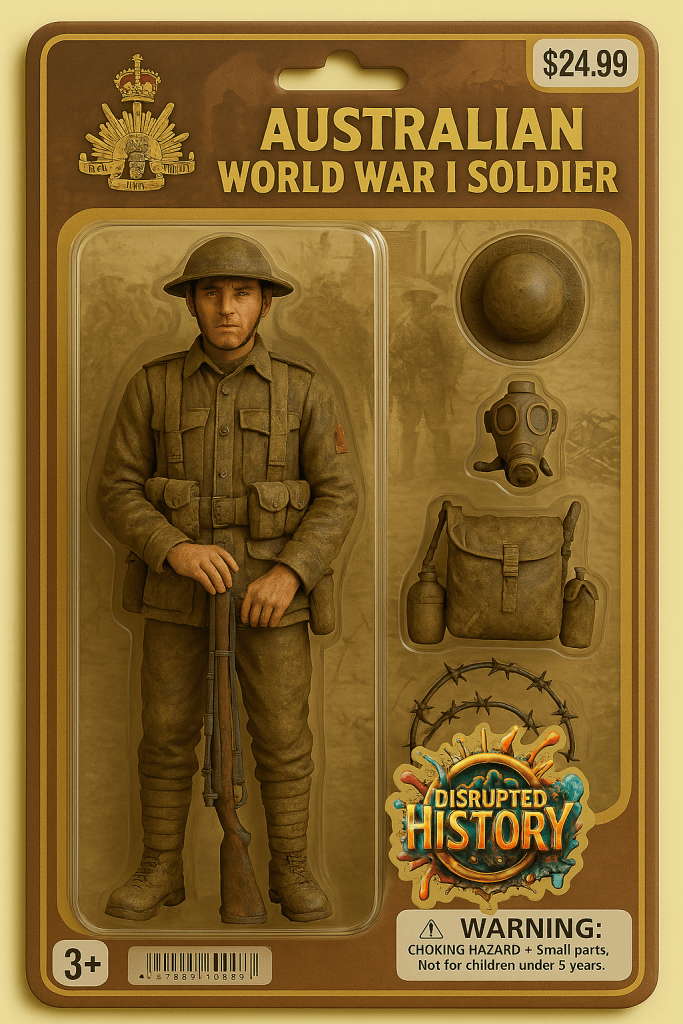

Create an Australian Western Front ‘digger’ from World War 1

I am a teacher experimenting with the potential for historical learning in the creation of AI-generated action figures. I am interested in the ways colour, symbols, words, and other elements of design in toys might shape historical representations. Create a historically accurate action figure of Australian soldier from the trenches of the Western Front of World War 1 in lifelike colour. The soldier is in his 20s but is battle-weary and aged. He wears the full uniform of an Australian soldier in the frontline trenches. His equipment is muddied and dirty. His uniform and kit reflect the conditions of trench life. The figure is posed as if relaxing during a lull in the fighting. Include modern vibrant toy packaging with Australian World War 1 emblems and symbols, use a khaki and brown toned palette, and use archival newspaper clippings in the background. The action figure doll must be full body length and in “3 dimensional” plastic as if a real children’s toy. It must include accessory toy parts and pieces that reflect the reality of a soldier’s experience on the western front such as British gas mask, helmet, barbed wire, weapons and other military kit. All items must be related to a soldier’s life and work in the trenches. They should reflect historical primary source photographs, archives, and Australian museum collections. Include realistic product packaging details including price, barcode, safety warnings and so on.

My prompt and the related multi-turn chat thread in ChatGPT is accessible here. [Note: I still wasn’t overly happy with this outcome!]

Final Thought: Play with Purpose

Used wisely, Generative AI doesn’t diminish the past – it challenges us to engage with it in new ways.

At first glance, these images may look like little more than play. They echo childhood moments – lining up action figures, projecting our imaginations into plastic bodies, animating inanimate objects with story and purpose. But when placed into the thoughtful hands of educators, and scaffolded through inquiry-driven routines, these stylised AI figures become more than just novelty. They offer a compelling entry point into what I argue in my research is transformative, reparative, and future-oriented historical thinking.

In this space – between the absurd and the analytical – we find the real power of generative AI in the History classroom.

This work aligns directly with what I’m working towards in my research and broader praxis: a technology-infused history pedagogy that enhances students’ civic, global, and personal agency. It is history education as meaning-making. It is a pedagogy that moves beyond transmission, beyond recall, and beyond the narrow confines of textbook timelines. Here, through creating action figures with the help of AI, students are not passive consumers of pre-packaged narratives – they are active participants in constructing, questioning, and reimagining the past.

To do this meaningfully, we must slow down.

In a time of accelerating technologies and performative productivity, the idea of slow teaching might feel countercultural – but it is precisely what our students need. Slowing down means creating space for reflection, uncertainty, ethical discomfort, and interpretive dialogue. It means letting students dwell in the messy middle of history: where sources contradict, where evidence is partial, and where meaning must be made rather than found.

These AI-generated images invite that kind of dwelling.

When a student is asked to create an image of Vida Goldstein, they must make choices: What sources will I rely on? What era of her life will I represent? Will she be speaking, or marching, or writing? What symbols, colours, or slogans do justice to her legacy? And what if my interpretation says more about me than about her?

These are not easy questions. But they are the right ones.

They encourage the kind of historical consciousness that Sam Wineburg argued is vital in a world of information overload and digital manipulation. They ask students to consider how knowledge is constructed, how memory is shaped, and how power operates in what is remembered—and what is forgotten. They align, too, with the reparative demands on history. History must do more than describe and analyse the past – it must offer space for healing, agency, and justice.

And crucially, these approaches teach with AI, through AI, and about AI all at once.

Rather than framing AI as a shortcut or a threat, we present it as a context to be navigated critically and ethically. Students must learn to use AI tools thoughtfully. Through using the tools of AI they can come to see that historical representations are never neutral, whether produced by a textbook, a government, a meme… or a machine.

This is what it means to teach history in the age of AI – not just with new tools, but with new questions, new responsibilities, and new possibilities.

It means offering students more than facts. It means offering them voice, agency, and purpose. It means imagining what a reparative, technology-infused pedagogy might look like when grounded in care, evidence, and justice.

And maybe – just maybe – it starts with something as deceptively simple as the nostalgic memories of a toy.

When we slow the process down, when we build prompts using structured routines, and when we foreground evidence, ethics, and cultural context, these playful images become powerful tools for historical thinking.

Because teaching history isn’t just about what happened. It’s about how we choose to remember – and represent – it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.