This Teacher’s Journal: Blog Post 12 | April 6, 2025

As the first Australia teaching term for 2025 closes, for this post I’ve paused to reflect on what I’ve learned from living a full ‘seasonal cycle’ of my teaching model. A lot has unfolded yet I keep returning to one resonant idea: slow teaching.

Slow pedagogy contends that while busyness is the bread and butter of academia, a hurried education can negatively impact deep learning – and perhaps even more importantly, diminish the joys of the learning process. (Fournier 2024)

I suspect that I will return to this idea from time to time in my blogs

In an AI-disrupted, VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) world, slow teaching is not about resisting technological change or romanticising the past. It is about presence and purpose – making space for deep connection, agency, and inquiry in a world increasingly defined by acceleration.

This disruption presented by the ubiquity of increasingly powerful AI may be the prompt we’ve needed to come back to process over product, to authenticity over superficiality, and to questions of why we teach, not just how.

It’s precisely because technology – and particularly AI – is so powerful and fast that slow pedagogy matters more than ever. Teachers must not respond to this disruption by teaching faster, producing more, or simply digitising old habits. Instead, educators are invited – perhaps even compelled – by this VUCA era into a rethinking of purpose. Technology is not an add-on or distraction; it is a force that exposes the cracks in education’s factory-era foundations. It reminds us that true learning isn’t about performative outputs or hollow productivity. It’s about meaning-making, complexity, reflection, and the slow unfurling of understanding.

Slow pedagogy in an AI-infused classroom is becoming an increasingly central focus of my work—and perhaps, where my praxis is quietly leading me.

These 9 reflections from the term trace that emerging trajectory.

Reflection 1: ‘We Are in 1750… and the Loom Is Now‘

The AI revolution is as disruptive as the Industrial Revolution. In 1750s Britain, weavers worked slowly and skilfully by hand—producing cloth through processes honed over generations. Then came the power loom: a machine that revolutionised production, displaced workers, and fundamentally changed the nature of their craft.

Some weavers resisted; others adapted. The textile industry survived, but it was never the same again.

Today, teachers stand in a similar moment. AI is our power loom—redefining work, roles, and relationships. Teaching will survive, but it will transform.

I am no Ned Ludd. I don’t reject AI or other technology. In fact, I advocate for its thoughtful and purposeful use – not to accelerate old habits, but to open up new possibilities for slow teaching. AI, when used wisely, can enhance deep learning, cultivate student agency, and make space for richer inquiry.

Slow teaching is one way to retain our humanity amidst the transformation. It insists on the value of community, critical thinking, and deep learning. It asks not just how we teach, but why. Slow teaching is one way to retain our humanity amidst the transformation. It insists on the value of community, critical thinking, and deep learning. It asks not just how we teach, but why.

Reflection 2: AI as Personal Tutor: Teach the Tool

AI, in the form of Copilot, Gemini, and ChatGPT, is ubiquitous in my classroom – often used by students as their personal tutor. I suspect it is even more present than I think.

Students are increasingly tapping into generative tools at school, at home, and beyond. But here’s the challenge: students don’t intuitively know how to hold a thoughtful, multi-turn conversation with an AI – just as many struggle to do so with humans. Their first instinct is too often to treat AI as a search engine, as a sort of vending machine for information. A usage characterised by asking a poorly considered question once, taking the first answer without reflection, and then moving on.

Teaching them how to engage meaningfully with AI is now a critical part of fostering their voice, agency, and thinking. Like any conversation worth having, it takes attention, engagement, time, follow-up questions, trial and error. It takes an ability to sit with, to dwell, in the discomfort of the unknown.

Slow teaching invites us to model and scaffold students’ engagement with AI. It encourages us to teach students how to prompt well, how to interrogate AI responses through clarifying questions and calls for elaboration or correction, and how to reflect – not for the sake of efficiency, but for the sake of insight.

AI, when taught as a tool to support inquiry, becomes a companion in the process of learning, not a shortcut to the end. In this way, slow pedagogy isn’t in tension with AI – it’s made more possible by it.

Reflection 3: Learning is Seasonal, Not Mechanical

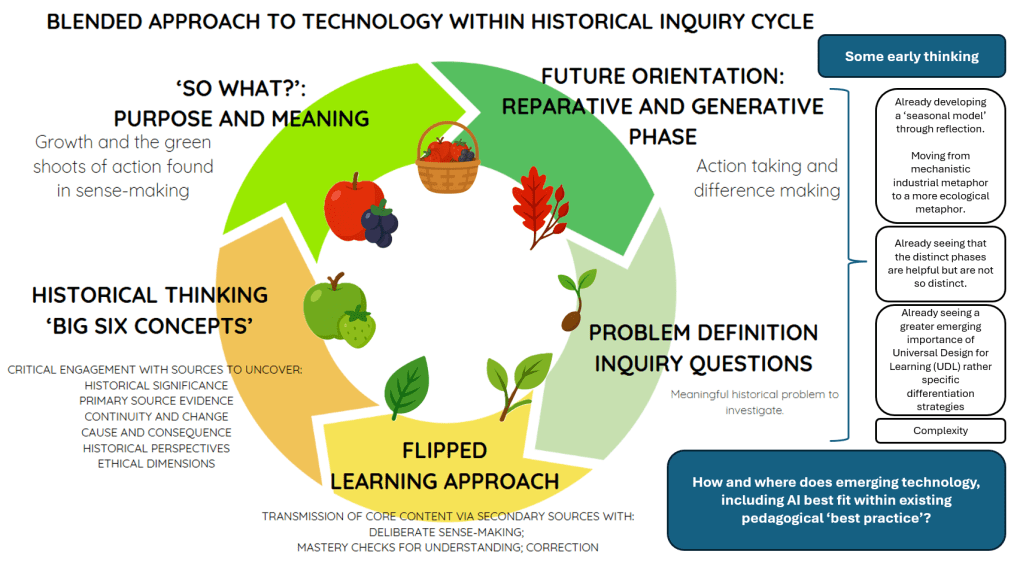

Historical learning does not move in clean lines. It ebbs, overlaps, revisits. Students don’t learn in perfectly ordered steps; they dwell, get stuck, surge ahead, and circle back. My model of the seasonal unit – unfolding in organic phases with blending transitions – helps me teach with an attuned ear, not a stopwatch.

This approach resists the mechanical logic of many school structures: fixed timelines, uniform assessments, content coverage checklists. Instead, it encourages me to observe how learning is growing, not just when it is delivered. Like the seasons, each phase of a unit offers something distinct: germination, growth, harvest, dormancy, renewal. Some ideas lie dormant for weeks before taking root. Others blossom early and scatter seeds for later reflection.

Slow teaching allows space for this natural rhythm.

It invites both teacher and student to lean into the cyclical, messy, recursive process of meaning-making. It reminds me that the role of a teacher is not to drive the train of curriculum at full speed – but to walk with students through terrain that changes with time, weather, and wonder.

Reflection 4: Flipped Pedagogy: Make Time for the Human

I’m working to make my flipped classroom a deliberately ‘slow’ space.

Students engage with teacher-made videos before class, complete checks for understanding, and then come together in live sessions for meaning-making, collaboration, and deep engagement with historical sources. These in-person moments are not an afterthought – they are the core of the learning experience, where complexity, community, and responsiveness thrive.

This approach mirrors what the OECD’s 2024 scoping review describes as the promise of flipped and blended learning for fostering higher-order thinking.

In a flipped approach, rather than receiving content in class and applying it alone outside of school, students arrive having encountered the material and use class time to actively discuss, apply, and extend their understanding.

This model not only allows for more interactive, collaborative learning – it can also foster creativity, critical thinking, and metacognitive reflection when paired with feedback and intentional design.

Studies cited in the review suggest that flipped learning, when structured thoughtfully, results in higher academic performance, greater creativity, and stronger higher-level thinking outcomes. It’s not just efficient—it’s transformative.

For me, flipping is not about offloading content but about reclaiming the classroom for human connection.

In an AI-infused flipped space, I can be more responsive to students’ questions, curate meaningful discussion, and support their thinking in real time.

I see potential in an AI-infused flipped learning approach to deliver a slow teaching pedagogy for history at its best: purposeful, relational, and attuned to the needs of the learners in front of me. A pedagogy that is transformational, generative, reparative, and future-oriented.

Reflection 5: Universal Design for Learning (UDL): Teach to All

Differentiation thrives within a thoughtfully inclusive design, but I am increasingly drawn to the distinction between differentiation and Universal Design for Learning. Where differentiation often starts with a ‘typical’ learner and then adjusts, UDL begins at the margins and plans inclusively from the outset. It’s a philosophical and practical shift: from patching to designing.

A slow pedagogy honours this approach. It resists one-size-fits-all timelines and assessments, and instead insists on thoughtful, intentional planning that embraces learner variability and cultivates student agency through multiple modes of access, representation, and engagement.

I’m finding that an AI-infused, flipped model of teaching history is particularly well-suited to a UDL framework. The flexibility of asynchronous video content allows students to pause, rewatch, or engage at their own pace. AI tools can be used (when guided ethically and reflectively) to provide personalised support -scaffolding inquiry, offering just-in-time feedback, or helping to generate ideas. In-class time then becomes a space where all learners can collaborate, ask questions, and explore concepts in ways that make sense to them.

To me, UDL through a model of slow teaching that is enhanced by AI and flipped learning approaches is not about reducing challenge – it’s about removing unnecessary barriers. It’s about building an environment where all learners, regardless of background or need, can enter into the rich, layered, and meaningful work of historical thinking.

Reflection 6: Risk Through Ill-Defined Challenges – Finding the Messy Middle!

Over-scaffolding robs students of uncertainty – the very condition in which creativity and growth can flourish. In my teaching, I am learning to be more comfortable in presenting to my students more ill-defined, low-stakes challenges that allow them to test ideas, linger, problem-solve, reflect, explore, to make decisions, and to take intellectual risks. This kind of slow challenge – authentic, ambiguous, and student-led – builds confidence and fosters historical thinking far more than neat rubrics ever could.

In our well-intentioned efforts to support learners, we can too easily end up scripting their experiences of the classroom and limit their thinking, leaving little space for curiosity, struggle, or self-direction. Students need to be provided with opportunities to not simply to apply knowledge but to wrestle with ambiguity, nuance, and perspective.

Nick Jackson’s recent writing on assessment culture helped crystallise something I’ve observed too: students often retreat to what they know – not out of preference, but out of conditioning. Years of standardised tasks, rigid rubrics, and high-stakes expectations have taught them that safety lies in certainty. We shouldn’t mistake this for a lack of imagination. It’s a symptom of an education system that rarely rewards open-ended exploration.

An AI-infused flipped pedagogy has the potential to support forms of slow teaching that interrupt this pattern of conditioning. When we offer students time, space, and permission to dwell in complexity – without rushing to (or even needing) a polished product – they begin to unlearn the need for immediate and superficial shows of ‘correctness’.

This kind of slow challenge – authentic, open-ended, and student-led – builds confidence and fosters deep historical thinking far more than neatly packaged rubrics ever could.

It cultivates agency not through control, but through supported experiences that engender self-confidence. And it reminds us that sometimes, the most powerful learning emerges in messy middles – not at tidy ends.

Reflection 7: Assessment as Performance: A Shallowing to Avoid

The moment summative assessment looms, the classroom climate shifts. There is a tightening. Curiosity and exploration often give way to a shallow performativity and compliance.

Well-intentioned hard scaffolding – intended to support – can become a cage, limiting thinking to what fits neatly into boxes. The language of risk, creativity, and possibility gets replaced by that of ‘requirements,’ ‘marks,’ and perceptions of ‘right’ and ‘what the teacher wants.’

In these moments, I’ve seen students who were previously confident, expressive, and agentic begin to second-guess themselves – seeking safety in formula. We must ask ourselves: what kind of learning are we measuring, and what kind are we unintentionally diminishing?

Slow teaching offers an alternative. AI-infused flipped approaches offer a possible pathway to slow teaching.

It treats assessment not as a culmination, but as part of an ongoing, dispersed process of thinking, reflecting, revising, and becoming. It allows for pause and for practice. It prioritises authenticity over polish. And perhaps most radically, it challenges us to reconsider when, how, and why we assess at all – not to abandon accountability, but to reclaim meaning and depth in what we value.

Reflection 8: AI as Disruptor: Assessment Must Change

AI disrupts everything: the already questionable conceptualisation of traditional homework, notions of authorship, modes of traditional take-home assessment. Yet many educators still operate as though business-as-usual will hold. It won’t.

This is not a cause for panic. It’s a prompt for transformation. AI has exposed the fragility of assessment-as-product and has revealed just how much of schooling depends on performative outputs. When the product can be outsourced, we are left to reckon with what we were actually trying to assess.

Slow teaching doesn’t mean resisting AI – it means using it wisely, ethically, and reflectively. It demands we reimagine assessment as a meaningful, ongoing process of becoming, not a one-off product. Authentic messy middles, not artificial tidy ends.

Slow teaching helps us respond with care rather than fear. It invites us to reimagine assessment as an integrated process: grounded in dialogue, shaped by feedback, and responsive to real-world thinking.

In a flipped, AI-aware classroom, assessment might look like students using AI to help refine ideas, while documenting their thinking along the way. It might involve collaborative projects, iterative drafts, or reflective oral defences. It might mean prioritising process portfolios over final products.

This is not about catching students out. It’s about asking better questions.

Questions that AI can’t answer for them. Questions that are uniquely human. Questions that matter in our soul.

The future of assessment will not be secured by guarding gates – it will be shaped by opening new paths to meaning.

Reflection 9: Post-Assessment Time is Precious

Too often, the time after summative assessment is devalued – as if learning stops once marks are assigned. Classrooms enter a kind of suspended animation: tired teachers focus on the work of grading, resources are packed away, student and teacher energy dips, and the space is quietly labelled by implication ‘non-essential’. This is sad to me. I’ve found that this time can hold something rare – something precious.

These ‘in-between’ spaces offer a chance to breathe, reflect, and re-engage with learning in freer, more expansive ways. Without the looming weight of grades or deadlines, students often open up – to ideas, to each other, and to the learning process itself. This is a time to seed new ways of thinking, to continue the season of learning.

This term, my Year 10 History class finished the term by connecting to the life lessons proffered by Holocaust survivor Eddie Jaku. Freed from the performance pressures of assessment, students engaged deeply and personally with his story. They began reading his book. The sat with the unknown, the uncomfortable, and the real. Their reflections were softly moving, their conversations thoughtful, their empathy real. Their preparation for the work of their next unit rich and authentic.

Slow teaching encourages us to treat this time not as filler, but as fertile ground. It is an opportunity for connection, consolidation, and extension – for storytelling, celebration, and shared meaning.

The post-assessment period of a term is a moment to bring learning full circle or to sow seeds for what comes next.

We should plan for it, protect it, and make the most of its quiet potential.

An Extra (10th) Reflection: Digital Literacy is a Civic Literacy

Students need more than knowledge and skills – they need wisdom.

In a world of information abundance, where information flows endlessly and algorithmically, knowing how to know has become a civic responsibility.

This includes understanding privacy, data security, search strategies, bias recognition, and lateral reading. But it also includes the critical dispositions to question, to verify, and to slow down when faced with the overwhelming speed and surface of digital content.

Teaching these literacies cannot be rushed or disconnected. It must be deliberate, embedded, and authentic. A slow teaching approach enables exactly that. By using an AI-infused flipped classroom approach, I am trying to ensure that all students have time for developing digital literacy in the context of their learning.

By being able to engage with content outside class, space in lesson time is freed up to allow for coaching in, and experimenting and practice of, real-world digital reasoning. Developing search terms, reverse image searching, evaluating online sources, comparing claims, examining contexts, verifying authorship and so on are part of the classroom experience – not as exceptions but a everyday ways of working.

Generative AI tools are part of this digital ecosystem. When used reflectively, they can serve as catalysts for discussion, inviting students to critique outputs, revise prompts, and trace how algorithms frame knowledge.

This is not a bolt-on to the history curriculum – it is the history curriculum. Teaching students how to think critically in digital environments is core historical thinking: sourcing, contextualising, analysing, evaluating, corroborating, and questioning.

The study of history in schools has always served a civic purpose. In a flipped, AI-infused history classroom, digital literacy therefore must be more than ‘a just skill’, just a checkbox of the general capabilities within the Australian Curriculum. In the study of history, digital literacy – it is a civic act.

In the AI age, digital literacy becomes a civic literacy. And teaching it slowly, with purpose, may be one of the most vital acts of citizenship we can offer.

Slow teaching gives students the time and space to question, verify, and reflect – essential habits for navigating truth in a noisy, fast-paced world.

Disruption, Design, and the Deeper Work of Slow Teaching

We may be living in a moment as consequential as 1750. Then, steam powered machines reshaped how people worked, lived, and learned. Today, AI is doing the same as it calls into question many of our taken-for-granted assumptions about the nature and purpose of schooling.

This is not a future to be feared, but it is a historical moment to be met with care.

In the Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous (VUCA) world that AI is creating for us, our work as educators has been disrupted. We can no longer imagine that the work of schools is simply about delivering content or preparing students for standardised endpoints.

Crucially modern schooling must embrace a mission of cultivating humanity’s discernment, adaptability, creativity, and civic responsibility.

Teaching must be about helping young people find meaning, voice, and agency in a world full of noise, automation, and uncertainty.

That’s why I’ve been drawn to slow teaching – not as an act of resistance against technology, but as an act of renewal. The disruptive power of Generative AI is opening an opportunity for education to ‘do more’ and ‘be more’. It holds promise for a better tomorrow beyond performativity and superficiality.

The how of this work matters. An AI-infused, flipped learning model – designed to incorporate the principles of Universal Design for Learning – offers new and necessary pathways to support all learners. It allows students to engage in learning on their terms, at their pace. It opens space in the classroom for dialogue, collaboration, and critical inquiry. It helps us reimagine assessment as something formative, reflective, and authentic – not just a product to be produced, but a process to be lived.

And the why? That remains constant: to support students in becoming thoughtful, discerning, ethical, engaged, and active citizens. In a world where AI can generate answers, our task is to help young people learn how to ask better questions -questions that connect, challenge, and change.

These reflections are just the beginning. My praxis is still evolving. But this much is clear: the disruption of AI is not the end of history education. It is a chance to reimagine it—more inclusive, more humane, more oriented to the future our students will inherit.

And that future demands we teach slowly, wisely, and with purpose.

Postscript: Praxis in Motion

This week I completed my Confirmation of Candidature panel presentation – an important milestone in my doctoral journey. Many of the ideas that have emerged in this post are still bubbling away from that process: unsettled, generative, and quietly reshaping the way I think about my teaching and research.

These reflections sit at the heart of my inquiry into a technology-infused, transformative history pedagogy. My work explores how AI-infused, flipped, and inclusive approaches can foster civic, personal, and global agency in students. Each entry in this blog is more than anecdote; it is a moment of praxis – an attempt to live the questions of my research in real classrooms, with real students.

This is not a finished model. It is a pedagogy still becoming. And these words are part of that becoming.

Thank you to all who have supported and encouraged me on this journey—your feedback, questions, and care continue to shape the work.

NOTE: Images in this post have been created with the assistance of AI. The diagram of a seasonal model is a conceptual diagram from my Confirmation of Candidature panel presentation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.