Offering interactive Vietnam War mind maps through study guides to personalised audio and video summaries, Google’s NotebookLM is reshaping how my History students study – even on the move. In this post, I reflect on what happened when I introduced it to Year 12 Modern History, and how one Year 9 student showed me how far in front of others she was by listening to AI-generated overviews of historical topics while jogging. It’s a glimpse into a future where learning doesn’t stop at the school gate – and where inquiry meets agency, one step at a time.

It’s been a little while between blog posts, and that’s not because there hasn’t been anything to write about. Quite the opposite. Since the start of the US school year in August, a range of products and product updates have dropped. It’s a job to just keep abreast of them! Also, over the past few months, my time has been absorbed in four overlapping streams of work, each of which has pushed my thinking in new directions:

- First, I’ve been drafting an article I hope to submit for peer review soon. It explores how we might thoughtfully sequence and scaffold student use of generative AI in the classroom — not just as a tool, but as a developmental process that shifts over time depending on student needs, readiness, and context.

- Second, I’ve been collaborating on a piece that documents the remarkable work of a colleague who is reimagining assessment in Years 8 and 9 English. Their work integrates AI within the learning process — not as a shortcut or substitute, but as a catalyst for reflection, redrafting, and deeper engagement with language.

- Third, I’ve taken a deep dive into Explicit Instruction (EI), especially through the lens of Sweller’s work on “guidance fading” and the “expertise reversal effect”. These aspects are often overlooked by some of EI’s most vocal proponents — in much the same way they sometimes understate the substantial role teachers play in Deweyan, inquiry-based history pedagogy. The kind of inquiry happening in history classrooms — particularly those aligned with Seixas and Wineburg — is not “minimal guidance” discovery learning. It’s structured, sequenced, and intellectually rigorous. The application of the interface of Sweller’s studies with those of Dewey, Seixas, and Wineburg for use in AI-infused classrooms is fascinating!

- Fourth, and perhaps most profoundly, I’ve been reflecting on what it actually means to use AI ethically in education. Like many, I often say we must use these tools ethically — but I’ve come to realise that I rarely explain what I truly mean by ethics and how it might translate into practice. I suspect that I might assume that we’re all on the same page when understanding ethics. There’s a deep and obvious flaw in that! In reading deeply around AI ethics, I’ve had to interrogate my own values, assumptions, and the ethical frameworks I bring to my classroom. These aren’t just abstract concerns. They shape how I guide students in navigating a world saturated with intelligent systems. They shape how I teach history, not just how I teach with AI.

What is NotebookLM?

Amidst all this, I’ve also been piloting the use of Google’s NotebookLM in my classroom — and the results have been both surprising and energising.

NotebookLM (short for Notebook Language Model) is Google’s AI-powered research assistant. It allows users to upload documents – PDFs, notes, articles, interviews – and then ask questions directly of that material. Unlike traditional search engines or even ChatGPT, NotebookLM doesn’t pull in generalised information from the internet. It restricts its responses to the documents you’ve chosen to include in your “notebook.” That means students can engage deeply with source material selected for or by them in a variety of ways all within a single interface.

And crucially, thanks to recent updates in our school system (and in recent platform changes and licensing arrangements of the big tech companies such as Google), our students now have access to school-managed accounts via school tenants that grant them secure, educational access to these tools. The platforms now available to my students are:

These student accounts are protected under Australian data privacy laws. When students log into Gemini or NotebookLM using their school credentials, all interactions stay within the Australian-based servers of those companies – and none of the data is used for training large language models. This is critical. It often worries me to hear about schools using AI platforms with students (under the age of 18) where these protections are not in place. Having these protocols in place via these two platforms means, at my school, we can begin to explore generative AI in my history classroom ethically, securely, and equitably – all students can use AI within my classroom with protections in place that respect student privacy and uphold professional standards.

Introducing NotebookLM to Year 12 Modern History

When I introduced NotebookLM to my Year 12 Modern History class, most students had never heard of it. Those who had didn’t realise what it could actually do. That’s not surprising – it’s a tool hiding in plain sight… but separated from their Google Gemini and Microsoft Copilot accounts.

So, I walked them through it.

Remember: Students aren’t really digital natives – at least not in the way many people sometimes assume. They are only familiar with the tools they’ve been exposed to. The myth of the inherently tech-savvy teenager doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. If we want them to use powerful tools like NotebookLM with fluency and discernment, we have to teach them. We have to make the invisible visible. And that’s not just about functionality – it’s about ethics, agency, and critical engagement.

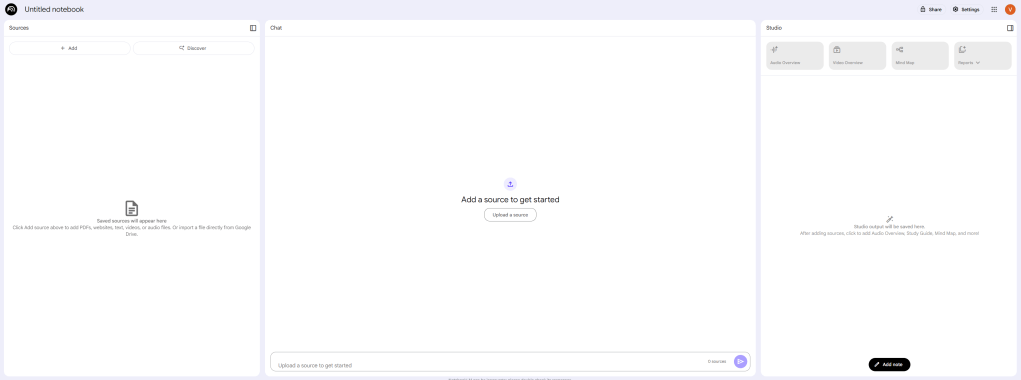

I showed them something they hadn’t expected – the NotebookLM Studio. This section of the platform allows students to generate:

- 🧠 Mind Maps

- 🎧 Audio Overviews

- 🎮 Video Overviews

- 📊 Reports

I took the opportunity to reinforce the core principle that AI-generated content needs to be critically evaluated – even by the platform’s own standards. NotebookLM reminds students to verify outputs and think for themselves. That aligns perfectly with what we already teach in Modern History: that sources must be questioned, not just consumed.

We started by uploading one of our classroom handouts – a set of background readings on the background to a study of Australia’s involvement in Vietnam War. Once uploaded into NotebookLM’s “Sources” panel, the AI could then engage directly with that document. We could use the NotebookLM Chat panel to ask it to summarise the key arguments, contrast differing perspectives, or even generate potential exam-style questions. And when we did, the AI’s responses were linked directly back to the original text.

Students then saw how quickly they might generate their own study resources in Studio. This genuinely opened eyes. The idea that students could take a classroom source and automatically produce a study-ready mind map, a podcast, or a concise video overview – all while retaining ownership of, and confidence in, the original materials – gave them a new sense of autonomy.

From Handouts to Mind Maps

To demonstrate NotebookLM’s potential, I showed the class what it could generate using just the multiple PDF handouts we’d uploaded.

First up was the Mind Map tool.

NotebookLM Studio was used to analyse the source material and produced an visual representation of the key themes and connections – an AI-generated interactive concept map that helped surface the internal structures of the reading. This isn’t just a gimmick. This tool creates a scaffold that students can use to support their ideas. This mind mapping tool shouldn’t be used to replace student learning but to support it.

Video Overview: Explaining the Big Picture

Next, I introduced students to the Video Overview function. I walked students through how the AI synthesises uploaded materials into a narrated slide-style presentation, complete with supporting visuals and captions. I urged students to evaluate these materials and demonstrated that anything created in Studio can be remixed at any time. Many resources in Studio can also be engaged with interactively.

To show how the Video Overview function works in practice, I recorded a video for this blog post showing how I generated a video overview from one of our Year 12 units.

The full video created is located here for your perusal.

A remix of the video is provided below.

Learning on the Move: Audio Overviews

We then looked at the Audio Overview feature. NotebookLM takes the key points from the uploaded sources and produces a short, narrated summary – like a personal podcast episode, tailored to your uploaded materials.

It’s easy to imagine how powerful this could be in students’ revision: imagine creating an audio study guide for each unit and listening while commuting, exercising, or reviewing before bed. This opens interesting possibilities!

At the recent National Education Summit, an educator shared how her students listen to her generated podcasts while walking around the school – as part of a wellbeing strategy that embraces embodiment (a conversation for another day!).

One Year 9 student in particular showed just how seamlessly this fits into her life.

She told me that she regularly creates audio overviews using NotebookLM in a variety of subjects – and listens to them while going for a run!

There was something strikingly natural about the way she described this practice: not as novel or extraordinary, but simply how she studies.

That comment stayed with me. It became the image that shaped this post: history “on the run.”

The Audio Summary created in NotebookLM Studio in the demonstration is provided below.

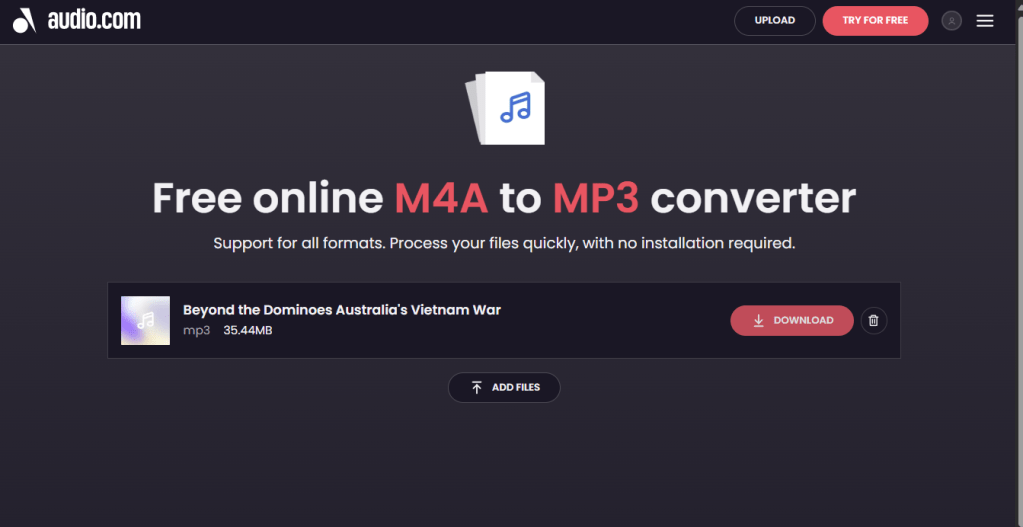

The file downloaded in an .m4a file type. To convert this to another file type, online free products exist. On this occasion I used audio.com’s Free online M4A to MP3 converter but you might like to experiment to find your own preferred converter.

DisruptedHistory.com doesn’t endorse any products such as this. At times, however, they are convenient!

Year 9s Were Already There!

The comments of the Year 9 student above were interesting for another reason. I had assumed, after teaching my Year 12 class about NotebookLM, that the Year 9s would also lack awareness of the NotebookLM tools. This was NOT the case! When I attempted to run a similar session to the one outlined above with my Year 9 History class, the experience was… different.

Many of them already knew about NotebookLM… and were using it extensively.

In fact, several had been quietly using it for months on private email logins via the personal Google accounts.. One student had created multiple notebooks to support her studies. Another, as mentioned, used the Audio Overview feature regularly – literally revising while doing athletics fitness training.

There’s something excitingly disruptive about that: a tool meant for researchers quietly becoming a study companion for 14-year-olds, guiding them in their own rhythms and routines.

Final Thoughts

NotebookLM is not a silver bullet for education. Like any tool, it must be used with care, context, and critical thought. But what it does offer is a new means for students to engage in their studies, to self-differentiate and to independently scaffold their learning. In the hands of thoughtful teachers and curious students, NotebookLM isn’t just a study aid. It’s an invitation to think deeply about their learning – in the classroom, in the community, and even on the run.

You must be logged in to post a comment.