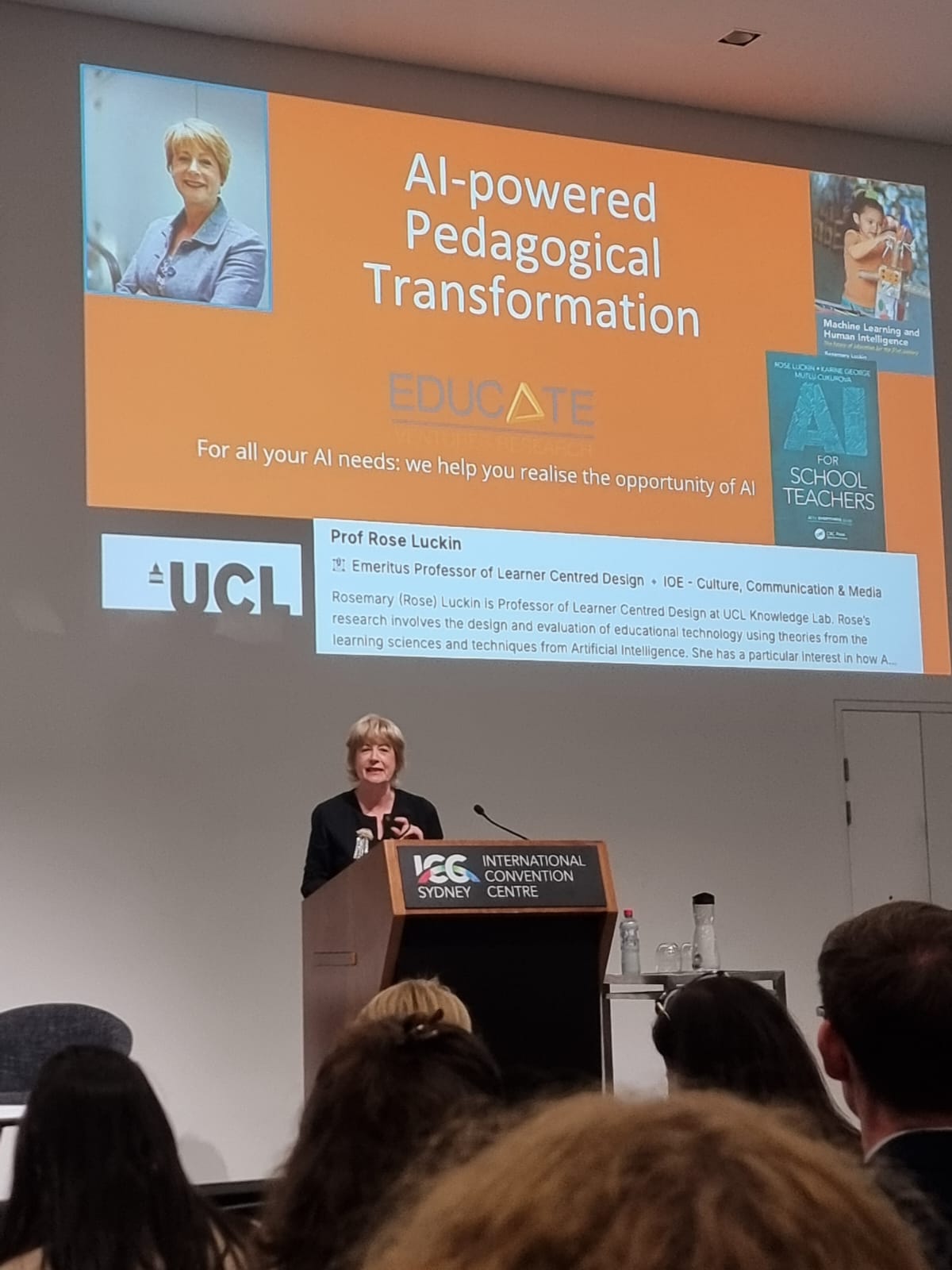

I had the privilege of hearing Professor Rose Luckin speak live twice at EduTECH Australia 2025, and while her reputation as a global authority on AI in education certainly preceded her, it was the clarity, urgency, and humanity of her message that resonated most powerfully. Her keynote was not a sales pitch for the latest tools or a technical showcase. Instead, it was a deeply philosophical and strategically grounded call to action for educators, school leaders, and system architects to engage with AI from a place of wisdom, not novelty.

Luckin framed the current AI moment as a “perfect storm” – a convergence of mass data availability, advanced algorithmic design, and exponentially improved processing power. This trifecta has rapidly reshaped not just the digital environment but the societal landscape itself. Against this backdrop, she argued that the transformation required in education is nothing short of fundamental. The systems, purposes, and logics of education must be rethought if we are to prepare students not just to live in this AI-suffused world, but to shape it. With AI reasoning models becoming more sophisticated and agentic AI now pursuing semi-autonomous goals, we are not facing a slow evolution but a dramatic shift within a very short timeframe. Waiting to respond, Luckin warned, is a dangerous luxury. Her message to educational institutions was clear: move beyond the “wait-and-see” approach. Visionary leadership must “pause, prepare, and partner” now if education is to serve as society’s most powerful tool for navigating this emerging terrain.

Luckin framed the current AI moment as a “perfect storm” but far from being a technophile’s dream, her analysis was human-first. She argued – convincingly – that the most critical infrastructure in this moment isn’t technical, it’s human. That using AI well means focusing on people and their agency, not on platform features. As someone researching how digital tools might support student agency in history education, I found this both affirming and energising.

There were several moments during her talk that gave me pause to reflect. First, her insistence that AI is about much more than productivity gains and workflow optimisation. Those were the easy, early takes of 2023. To hold onto those notions of AI is to miss the point. Those who lingerin that conceptualisation of Generative AI miss a true perception of the deeper transformative potential of AI – and its risks. She reminded us that even the creators of generative AI don’t fully understand the power of what they’ve unleashed. That reality should humble us, not paralyse us.

Second, Luckin’s call for a reimagining of assessment hit close to home. Speaking primarily to conference delegates from the higher education section in her second presentation, Luckin made clear that assessment systems rooted in 20th-century notions of control and content reproduction are already obsolete in the face of generative AI. Her critique of cognitive offloading – where learners hand over the hard work of thinking to AI tools – was not just theoretical. It was a call to redesign learning so that thinking, questioning, and ethical discernment remain central. This has powerful implications for history education, where student agency isn’t just about voice, but about judgement, historical empathy, and civic participation. There was urgency in her call for action in this area.

What also stood out to me, also, was Luckin’s strategic wisdom. She urged her listeners to: “Learn fast but act slowly”. This call did not contradict a sense of urgency in her call for action. It was an invitation to become rapidly literate in AI’s affordances and limitations, while implementing change with deliberation and care… not tardiness or hesitancy. “Learn fast but act slowly” is a call for actions that are not knee-jerk or panicked. A call for bravery and wisdom in leadership. A call for thought but not an excuse for the ‘paralysis of analysis’.

In my own action research, I’m exploring how to introduce generative AI into the history classroom in ways that are student-centred and transformative, not just efficient. Luckin’s framework – especially her call for visionary leadership and thoughtful, use-case-driven adoption – aligns strongly with what I am seeing on the ground.

Luckin challenged her audiences to stop asking, “What can AI do?” and to instead ask, “What do our students really, really need?” That shift is profound. In history education, this means thinking beyond source analysis skills and historical thinking rubrics. It means designing for action and agency: the ability of students to see themselves as actors in civic, community, personal, and global contexts. If AI can support that mission – and I believe it can – then it must be embedded not as a gimmick or bolt-on, but as part of a deeply ethical, reparative, and future-oriented pedagogy.

To me, Professor Luckin’s address wasn’t about fear, nor was it about hype. It was about leadership. And not just system leadership or EdTech leadership, but pedagogical leadership – the kind that sees every classroom as a site of possibility. I left feeling both challenged and affirmed. In my research and teaching, I want to help build a pedagogy that doesn’t just survive the AI revolution, but one that helps students shape it.

Disruption, after all, is only a threat if we fail to respond by failing to lead.

You must be logged in to post a comment.